A FRESH approach: Nutrition researcher partners with community organizations to tackle diet-related disease and food insecurity

Melanie Hingle, a professor in the School of Nutritional Sciences and Wellness, is working with El Rio Health and the Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona on an ongoing research project to help food insecure individuals manage diet-related illness.

Managing diet-sensitive diseases like type-2 diabetes and high blood pressure can be challenging under the best of circumstances. For individuals experiencing food insecurity, it can feel nearly impossible. The Food and Resources Expanded to Support Health (FRESH) project - an ongoing research collaboration between the University of Arizona School of Nutritional Sciences and Wellness (SNSW), El Rio Health and the Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona - hopes to change that.

The FRESH project combines culinary medicine and community-based healthcare to provide medically tailored food boxes and educational support to food insecure individuals who have or are at risk of developing diet-related disease. According to lead researcher and SNSW professor Melanie Hingle, the project builds on existing efforts by all three organizations, allowing them to share their resources and expertise.

“El Rio and the Food Bank have very similar client populations, and they were independently grappling with how best to serve clients who are food insecure and are trying to manage chronic, diet-sensitive conditions,” she said. “We wanted to develop something that would be responsive to those folks and what they needed, to make sure that the intervention would be appropriate for their nutrition needs, their preferences, and their life circumstances.”

Holly Bryant, El Rio’s Registered Dietitian Director, explained that addressing clients’ food insecurity is essential to helping them manage their health conditions. “Chronic diseases like type-2 diabetes are impacted by how we eat, and how we eat is impacted by what food we have access to,” she said. “Food access is one of the major social determinants of health. If you can’t afford healthy foods, or if you don’t have the time, space or tools to prepare them, it’s much harder to eat in a way that helps promote health.”

Food is medicine

Central to the FRESH project is the concept of “Food Is Medicine” (FIM). The term , now embraced by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, describes a broad range of approaches designed to prevent diet-related disease and promote optimal health by providing nutritious food and nutrition education as a form of healthcare.

Hingle, whose work sits at the intersection of nutritional sciences research and public health practice, visualizes the types of FIM as a pyramid. She puts the least-intensive, broadest-reaching approaches – like providing nutrition labels on foods – at the bottom, and interventions like professionally prepared meals that have been medically tailored for patients going through cancer or HIV treatment at the top.

“The FRESH project sits somewhere near the top of the pyramid, with medically tailored groceries that have been put together specifically for people with a certain condition – diabetes, in our case,” she said. “It’s more intense than something like SNAP or WIC, because even though we’re also serving low-resource individuals, our clients have the added complication of needing to manage their chronic conditions.”

A responsive intervention

The FRESH project is now in its second iteration, a clinical trial that will track how participants use the program, how participation affects individual health outcomes and whether participation affects their utilization of the healthcare system.

“We learned a lot from the first phase, which was a small feasibility study,” said Hingle. “That allowed us to apply for funding from the National Institutes of Health so we could more robustly test this kind of intervention. It also gave us the opportunity to make tweaks to the program to make it more responsive to our participants’ needs and preferences.”

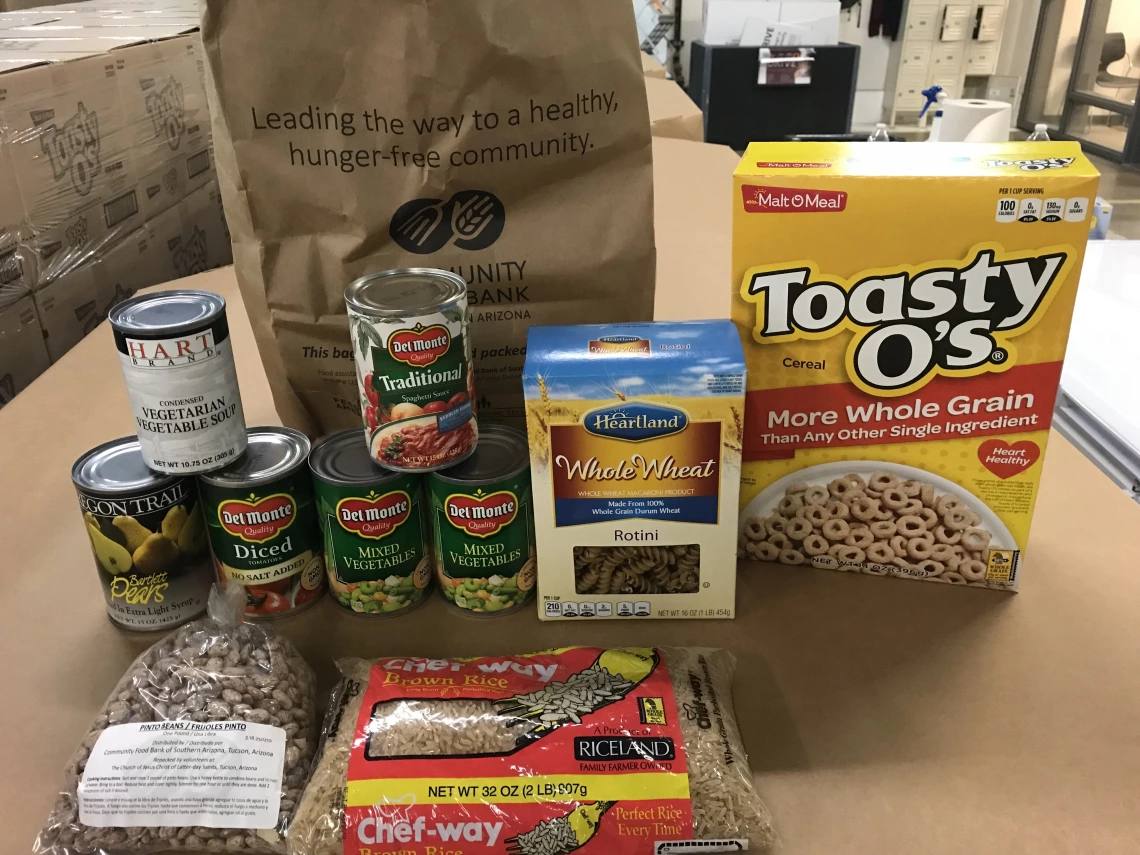

FRESH program participants receive bi-monthly food packages, provided by the Community Food Bank. The packages contain groceries that meet American Diabetes Association nutrition therapy recommendations, recipes that incorporate those foods and educational materials about managing diabetes. Participants can also meet with a registered dietitian, who can counsel them on diet modifications, food preparation and overall health goals.

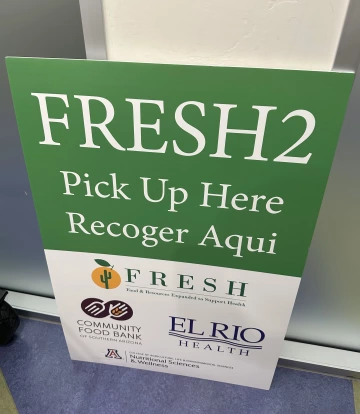

One change from the first FRESH study is that current participants pick up their food boxes at the El Rio Health Center, instead of having the boxes delivered to their homes. According to Bryant, this offers a one-stop-shop opportunity so that patients can attend a medical appointment, get referrals to specialists or meet with a community health advisor when they come for their food boxes.

“We’re trying to provide whole-person health care at El Rio,” she said. “When individuals pick up their boxes, they can also talk to the on-site dietitian about what’s in the box, and they can check in with the community health advisor about other services they may need, like housing assistance or help getting out of a domestic violence situation.”

Taking steps toward sustainability

While the clinical trial is ongoing, FRESH project organizers are already considering how to keep it going after this phase concludes.

“The FRESH project is a great opportunity to contribute to the research around food insecurity and diet-sensitive disease,” said Joy Mockbee, a primary care physician at El Rio who helped develop the intervention. “But this isn’t science in a lab, this impacts real life populations. The ultimate goal has always been to see if we can create a sustainable program that works for real people in the real world.”

According to both Hingle and Bryant, the chief hurdle to the program’s sustainability is the cost of food. Some states allow doctors to write food prescriptions that are then reimbursed through Medicaid, but that isn’t the case in Arizona. The FRESH team hopes to provide data that will help build a strong case for the benefits of this type of program, both for individuals and for the healthcare industry.

“Any kind of intervention has a cost, whether it’s paying for medications, hospital visits or, with a program like ours, food,” Hingle said. “If we can do a food-based intervention that mitigates a hospital visit down the road or allows people to reduce their prescription use, that’s a huge win – for the patients, and for the taxpayers who are contributing to the healthcare system.”

Related Video:

The FRESH Project was featured in a July 1, 2025 episode of Arizona Illustrated.

Related Video:

HHS Assistant Secretary for Health Adm. Rachel Levine speaks with SNSW professor Melanie Hingle about the Food Is Medicine and the FRESH Project.