|

|

Policy Development

![]()

For More Information

Background

Social change model

Educational intervention model

Evaluation of the Policy Development Process

Evaluating Implementation and Outcomes

Annotated bibliography

Internet Links

References

Background

Historically, policy development for children, youth and families focused

on defining problems at the individual level (usually deficits) and developing

interventions directed at the individual's problem. Policy makers assumed

that by changing individuals, their own and their families’ well-being

would be improved. But changes made to and by individuals do not occur

in isolation. They are part of other societal events and changes that

interact with the economy, trends, and shifts in national policy priorities.

An individual may change his or her behavior but due to other events,

he or she may not be a "better" position. For example, someone may complete

preemployment training and acquire job skills but remain unemployed due

to the lack of jobs.

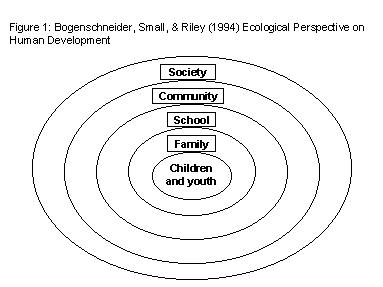

The relationship between children, youth, families, and communities can

also be viewed from an ecological perspective (NNFR, 1995, Bogenschneider,

Small, & Riley, 1994). Individual development and well-being are influenced

by one's interactions with family, community, and society in general.

Graphically, these relationships would be depicted by a series of concentric

circles showing children and youth at the center.

Policy development occurs at the community, state, national and international

levels. It has indirect effects on all the circles representing the human

ecology. Policies formulated at the state and national level impact policies

at the community level. For example, recent changes in federal welfare

policy have many implications for communities. Local decision-makers are

facing questions about the impact of “devolution.” More and more responsibility

for social welfare programs are being passed to the community from the

state and federal government. How do communities meet the welfare needs

of legal immigrants and create enough high-quality jobs for welfare recipients?

The kind of policy decisions made by communities on these issues will

impact the well-being of families, children, and youth now and in the

future.

Social Change Model

Policies are created at many levels in both the private and public sectors.

A community collaboration generally uses a planning process to determine

goals and an agreed-upon course of action that will positively impact

family and youth development (Zimmerman, 1995; Bogenschneider, Small and

Riley, 1994)

The Social Change Model (Figure 2) underlies policy development at the community, state and national levels (Zimmerman, 1995). In this framework, a novel situation often arises and becomes a catalyst for the development of policy. For example, recent increases in teenage smoking may be viewed as a novel situation that raises concern among health advocates, parents and others.

Figure 2. Social Change Model

Mobilization of

Competing perceptions

activity to

Novel ==> and definitions of

==> support competing ==> Social

Situation novel situation

definitions

Action

The process moves to the next stage when individuals or groups emerge

to begin defining and interpreting the situation to others as they see

it. For example, one group may define the problem of teenage smoking as

a lack of parental control while another group may blame it on easy access

to smoking products.

This struggle over competing definitions leads to the next stage and takes

on a political dimension. Individuals or groups seek out politically significant

groups and try to persuade them to accept their definition and perception

of the situation. Groups can also be recruited or created at this stage

to press for social action.

The resulting action may create a new law or policy, a new institution,

organizational reform, or other actions. For example, a new law on restricting

youth access to smoking products may be created. If politically significant

groups had decided the situation did not merit attention, little may be

done to address the novel situation.

The model is circular because new actions will typically generate new

novel situations and the process begins again. Moving to the final stage

of policy development hinges on individuals or groups persuading politically

significant organizations and individuals to take some action. An important

component of the social change model involves identifying politically

significant individuals or groups and persuading them to accept the definition

and perception of the problem.

The Social Change Model has been used by many authors, (see annotated

bibliography: Chapin,1994, Hahn, 1992, Meehan, 1985, and Ramirez, 1995)

as a basis for conceptualizing the policy development process. Although

each author differs in the number of steps involved in the process all

identified similar components.

Educational Intervention Model

The Educational Intervention Model developed by Hahn (1992) provides a

useful guide for TCPs when planning policy education strategies and developing

policies supportive of children, youth and families. Figure 3 outlines

the stages of this approach. Although the stages are numbered, the process

is not linear. For example, in Stage 3 when the issue is defined, the

group may agree that additional members are needed. The group would then

return to Stage 2 to seek additional individuals and return to Stage 3

to involve the new members in the issue definition. Also, if someone is

seriously dissatisfied with the choice at Stage 6, the process may return

to Stage 4. After the results are evaluated in Stage 8, the entire process

often begins again.

Figure 3. Hahn's Educational Intervention Model

Stage 1 - Concern Someone identifies a concern, problem or vision of

how things could be better.

Possible Activities: Conduct community assessment Review research literature

for more information and possible solutions

Stage 2 - Involvement People with a concern seek additional support and

perhaps establish contact with decision makers. Additional people may

become involved. Opposition may also arise in this stage.

Possible Activities: Identify agencies, organizations and individuals

who might be helpful Establish a task force or collaboration Assess training

needs of task force members Determine supporters and non-supporters Contact

policy makers

Stage 3 - Issue

An issue is defined on which people can agree. However, there may not

be agreement on what should be done about the issue.

Possible Activities: Develop vision and mission for group Document and

disseminate alternate views on the issue Help clarify the issues through

discussion

Stage 4 - Alternatives

People seek and propose different ideas about what should be done to resolve

the issue.

Possible Activities: Generate alternatives through brainstorming or nominal

group process Seek objective information on alternatives Facilitate communication

and exchange of viewpoints

Stage 5 - Consequences

Alternatives are evaluated and discussed in terms of anticipated consequences.

Possible Activities: Assemble and distribute objective information on

consequences of alternatives Help citizens make their own predictions

about consequences Hold public forums and discuss alternatives

Stage 6 - Choice

Different people try to influence policy makers. It may be decided to

forget the whole issue, respond to one group or another, or reach a compromise.

Possible Activities: Provide information about how the choice will be

made Inform citizens of opportunities for effective participation Sponsor

legislative education days

Stage 7 - Implementation

A decision is implemented.

Possible Activities: Conduct public information campaigns Provide information

about policy choice

Stage 8 - Evaluation

Results are evaluated.

Possible Activities: Assess outcomes of intervention.

Because policy develops over time, the process cannot be explained as

a simple unit or event (Hayes 1982). Instead policy development involves

a large number of decision points and usually a large group of participants.

The complexity of each of these two characteristics and their interaction

with each other shape policy formation but create difficulty in evaluating

policy development.

Evaluation of the Policy Development Process

Evaluating policy development is not an easy task, but necessary in order

to communicate to policy makers and citizens the purposes, reality, and

accomplishments of the policy development process. Dale and Hahn (1994)

identify several benefits of evaluation for the policy development process.

Evaluation provides information to program implementers that will help

them adjust the program to better meet goals and provide valuable lessons

for future work. It identifies project impacts and helps participants

experience satisfaction about their accomplishments.

Evaluating Implementation and Outcomes

A good evaluation begins at the beginning of the policy development process.

Long-term outcomes are not the only things to evaluate; implementation

strategies can also be evaluated. Reflecting on what has already occurred

and what is planned is useful throughout the process. Dale and Hahn (1994)

suggest asking questions to help determine:

| If the program goals are still relevant. | |

| What methods or activities are planned to reach goals. | |

| How the participants apply what they learn. | |

| What effect will the activities have on the goals. | |

| Whether adjustments in goals and/or activities need to be made. |

Evaluators need to determine what potential outcomes the evaluation

will measure. Will the evaluation measure:

| Individual changes or changes in policy issues? | |

| Predetermined outcomes or emergent outcomes? | |

| Acceptance of existing policies versus a change-oriented approach that seeks a more equitable participation? | |

| Short term, intermediate, or long-term outcomes? |

Evaluating the impact of policy development focuses on either the benefits

for individuals participating in the process or on changes in policy issues.

Historically, evaluations have focused on changes in individual knowledge,

attitudes or opinions, skills, and behaviors related to policy development

(Dale and Hahn, 1994). Evaluation of the impacts of new or changed policies

is also important although they are seldom evaluated. Dale and Hahn (1994)

suggest that one way to detect changes in issue resolution is to interview

individuals who are involved in policy decision making or will make judgments

about the impact of specific interventions. These individuals can help

identify the results of an educational intervention, identify specific

aspects of the intervention that led to these results, and reflect on

what would have happened if the intervention had not taken place.

One difficulty of evaluating impacts on issue resolution is the relatively

long time frame needed for developing policy. However, process models

like Hahn's eight-stage model provide a framework to guide evaluation

of policy development at the community level. Outcome indicators for each

stage help educators determine their progress toward issue resolution

and point to a need to shift to the next stage or previous stage.

Evaluators encounter these challenges when evaluating policy development

interventions:

| The complexity of policy issues and of the educational programs that address them. | |

| Programs that typically evolve and change during the course of their implementation. | |

| Absence of "tried and true" measurement techniques for most outcomes of interest. | |

| Difficulty in identifying and sampling all audiences that the educator hopes to impact. | |

| The need to support evaluation results with sound research methods. (Dale and Hahn, 1994) |

Evaluators can begin to address these challenges by employing rigorous

techniques for collecting and monitoring quality data such as: employing

multiple philosophical and value frameworks, triangulation techniques

of data collection and analysis, mixing qualitative and quantitative data,

and maintaining a data monitoring system to assure the quality of the

data.

References

Bogenschneider, K., Small, S. and Riley, D. (1994). An ecological, risk-focused

approach for addressing youth-at-risk issues. Madison, WI: University

of Wisconsin-Madison Cooperative Extension.

Chapin, R. (1995). Social policy development: The strengths perspective.

Social Work, 40 (4), 506-514.

Dale, D. and Hahn. A. (1994). Public issues education: Increasing competence

in resolving public issues. Task Force of the National Public Policy Education

Committee. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin-Madison Cooperative Extension.

Hahn, Alan J. (1992) Resolving Public issues and Concern through Policy

Education. Itchica, NY: Cornell University, Cornell Cooperative Extension.

Hayes, C. (1982). Making policies for children: A study of the federal

process. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Meehan, E. (1985). Policy: Constructing a definition. Policy Sciences

(18), 291-311.

National Network for Family Resilience, Family resiliency: Building strengths

to meet life's challenges. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Extension.

Ramirez, A. (1995). Powerful Policies. The American School Board Journal,

182 (12), 27-29.

Zimmerman, S. (1995). Understanding Family Policy, 2nd edition. Thousand

Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. ![]()

Indicators and Measures |

Other Tools |

Annotated Bibliography |

Internet links |

|

| Policy Development | |

||||

| Program Outcomes for Communities | |

||||

| NOWG Home | |

||||