< Back to Climate Viticulture Newsletter

Hello, everyone!

This is the October 2024 issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter – a quick look at some timely climate topics relevant to wine grape growing in Arizona.

IN THIS ISSUE

- A Recap of September Temperature and Precipitation

- The Outlook for October Temperature and Precipitation

- Dew Point and Diurnal Temperature Range

- Temperature Ranges and Ripening Period

- Extra Notes

A Recap of September Temperature and Precipitation

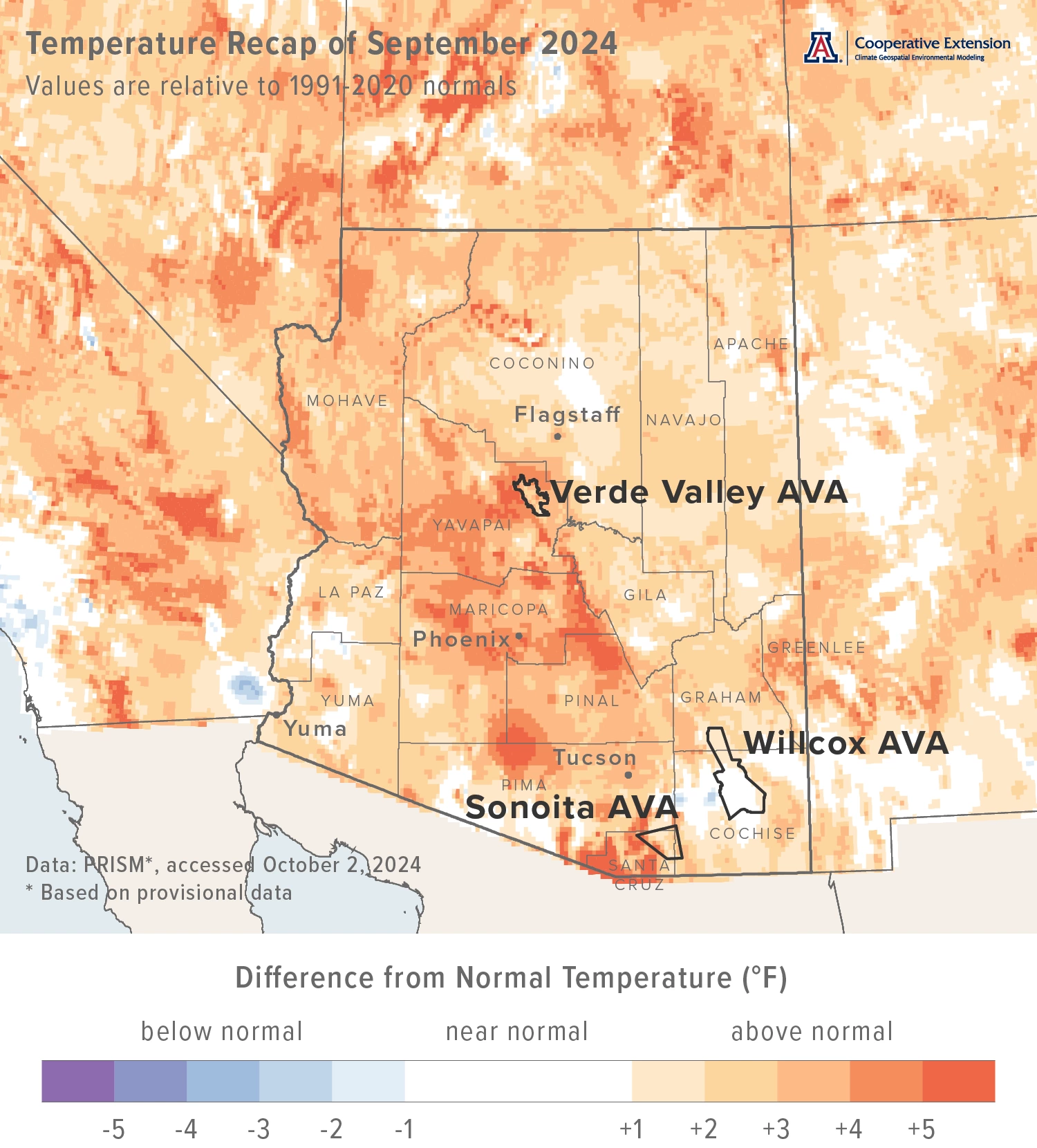

Monthly average temperatures were 2 to 5 °F above the 1991-2020 normal for most of Arizona (orange, dark orange, and red-orange areas on map), including the Sonoita and Verde Valley AVAs. A few locations in the state escaped the near-record and record-level heat with near-normal temperatures, like most of the Willcox AVA (white areas on map). For reference, monthly average temperatures in September last year were 1 to 3 °F below normal in northwestern Arizona, near normal for much of north-central and southwestern Arizona, and 1 to 4 °F above normal for many locations in central, east-central, and southeastern Arizona.

Area-average maximum and minimum temperatures during September 2024 were 87.7 and 59.3 °F for the Sonoita AVA, 96.1 and 59.8 °F for the Verde Valley AVA, and 89.6 and 58.1 °F for the Willcox AVA. Respective September normals are 83.9 and 57.0 °F, 90.4 and 58.4 °F, and 87.8 and 58.3 °F.

Temperature last month ranged between 97.2 and 47.5 °F at the AZMet Bonita station and between 98.6 and 45.9 °F at the AZMet Willcox Bench station.

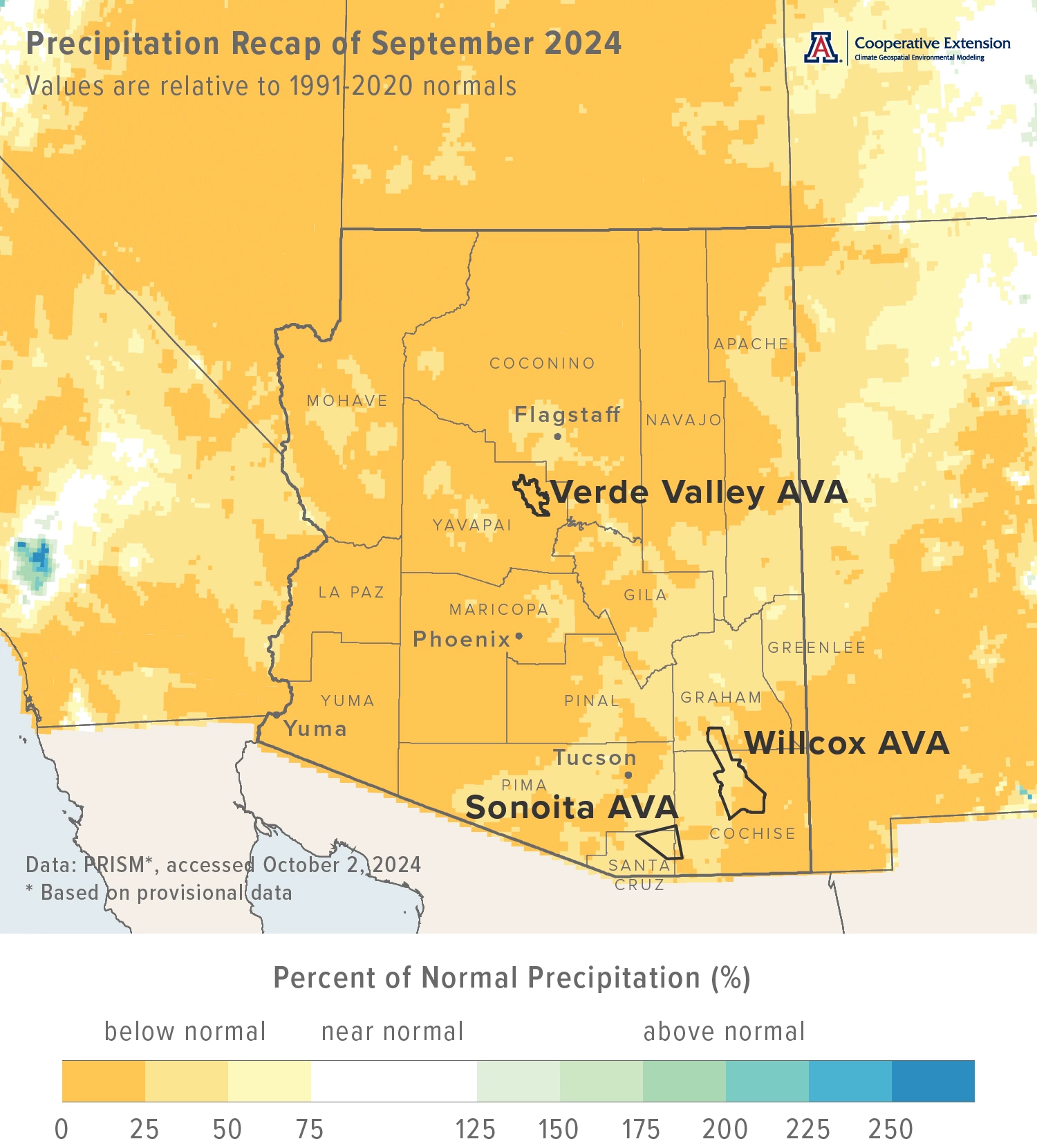

Jeremy Weiss

Monthly precipitation totals were less than 50 % of normal across the state (yellow and dark yellow areas on map), including all three Arizona AVAs. Precipitation during September 2023 was more than 150 % of normal for extreme western Arizona, and a mix of near-normal totals and totals between 25 and 75 % of normal for areas elsewhere in the state.

Area-average total precipitation in September 2024 was 0.60 inches for the Sonoita AVA, 0.18 inches for the Verde Valley AVA, and 0.34 inches for the Willcox AVA. Respective September normals are 1.95, 1.53, and 1.40 inches.

Total precipitation last month was 1.07 and 0.00 inches at the AZMet Bonita and Willcox Bench stations, respectively.

Dig further into daily weather summaries for the AZMet Bonita and Willcox Bench stations in the Willcox AVA

Learn more about PRISM climate data

Jeremy Weiss

The Outlook for October Temperature and Precipitation

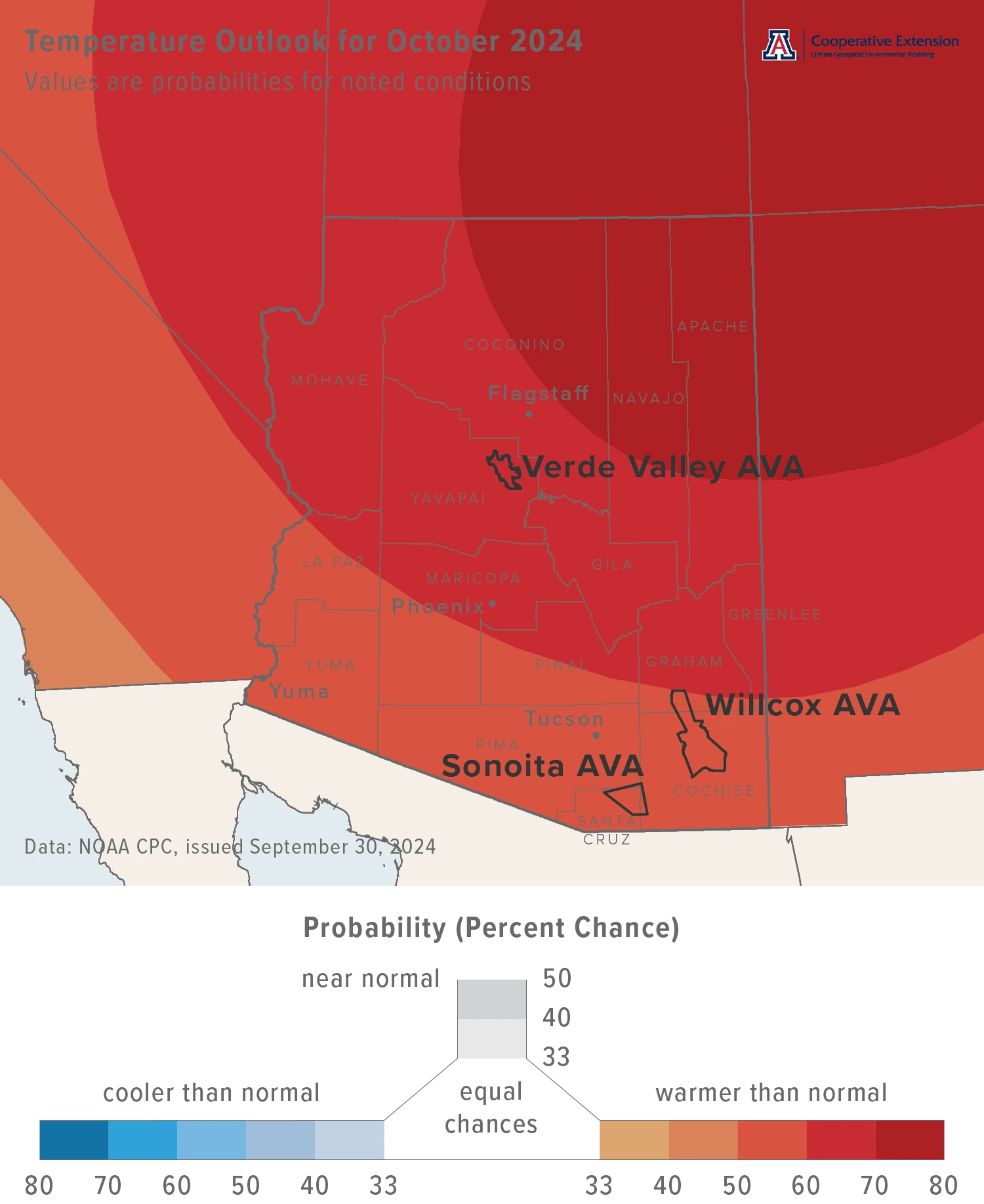

Temperatures over the course of this month have a moderate increase in chances for being above the 1991-2020 normal across all but the northeastern corner of the state (dark orange and red areas on map). For the northeastern corner, there is a strong increase in chances for above-normal temperatures (dark red area on map). Monthly average temperatures in October last year were 1 to 4 °F above normal for almost all the state, with several locations in the central and southeastern parts recording values more than 4 °F above normal.

Area-average maximum and minimum temperatures during October 2023 were 81.0 and 49.9 °F for the Sonoita AVA, 83.3 and 48.5 °F for the Verde Valley AVA, and 82.6 and 48.5 °F for the Willcox AVA. Respective October normals are 77.3 and 47.5 °F, 80.2 and 47.0 °F, and 79.9 and 46.8 °F.

Temperature in October last year ranged between 92.7 and 37.4 °F at the AZMet Bonita station and between 92.7 and 38.8 °F at the AZMet Willcox Bench station.

Jeremy Weiss

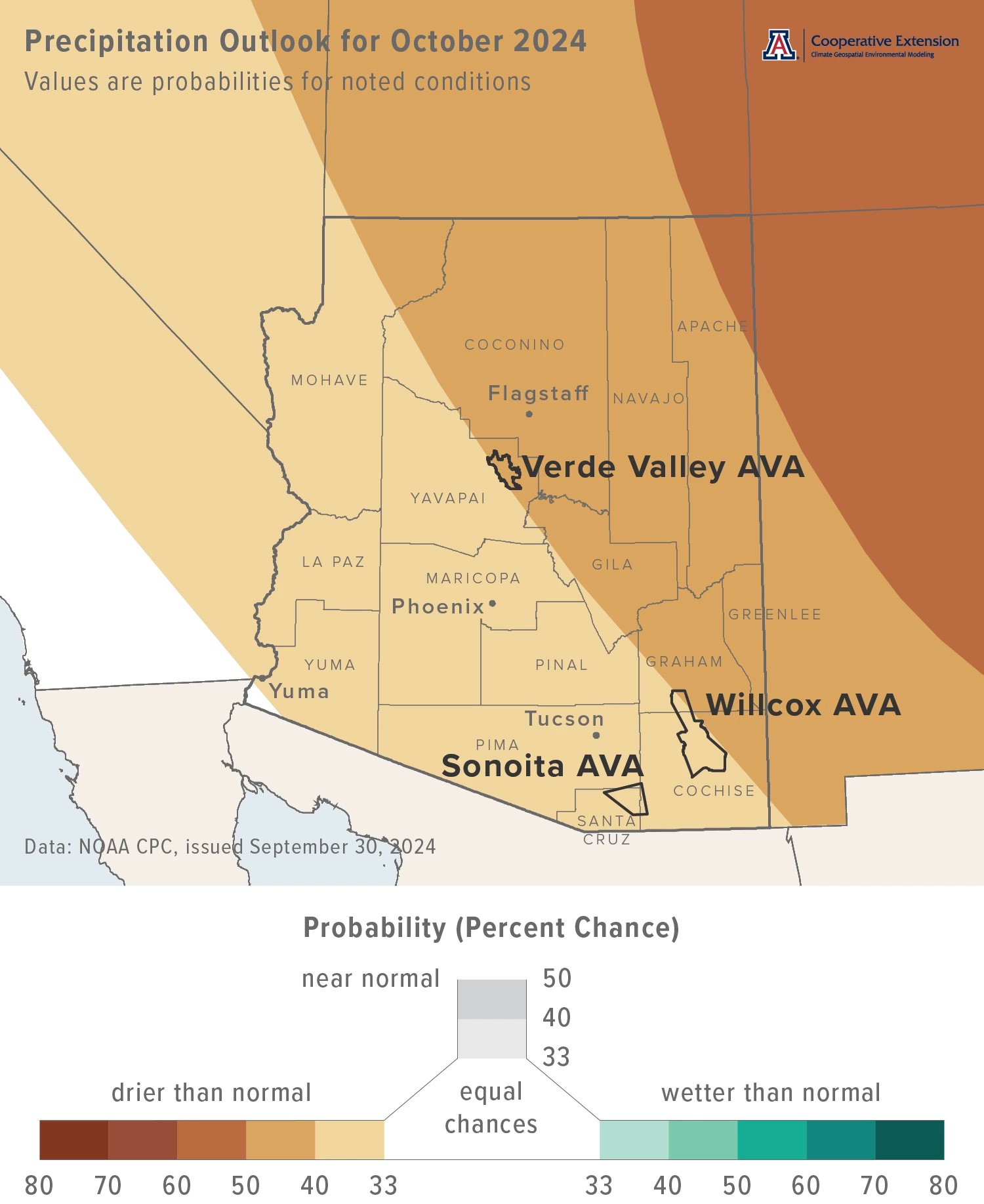

Precipitation totals for this month have a slight increase in chances for being below normal across all the state (light tan and tan areas on map). Precipitation during October 2023 was less than 25 % of normal for almost all of Arizona, with only some locations in the northeastern and southeastern parts of the state recording amounts between 25 and 75 % of normal.

Area-average precipitation totals in October 2023 were 0.22 inches for the Sonoita AVA, 0.03 inches for the Verde Valley AVA, and 0.26 inches for the Willcox AVA. Respective October normals are 0.95, 1.05, and 0.76 inches.

Total precipitation in October last year was 0.17 and 0.22 inches at the AZMet Bonita and Willcox Bench stations, respectively.

To stay informed of long-range temperature and precipitation possibilities beyond the coverage of a standard weather forecast, check in, too, with the six-to-ten-day outlook and eight-to-fourteen-day outlook issued daily by NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

Jeremy Weiss

Dew Point and Diurnal Temperature Range

We first ran this topic and the one in the following section this time last year, but thought it might be worthwhile to revisit with the addition of data from the 2024 ripening and harvest season.

With the monsoon comes a number of changes in growing conditions from June through September, and these changes often coincide with ripening and harvest. We’ve looked at this in a number of newsletter issues over the past few growing seasons, noting the potential effects of temperature or, more recently, precipitation on fruit quality and composition. Here, we take a different tack and compare the increase in humidity at this time of year and coincident temperatures to unpack what the monsoon does to diurnal temperature range.

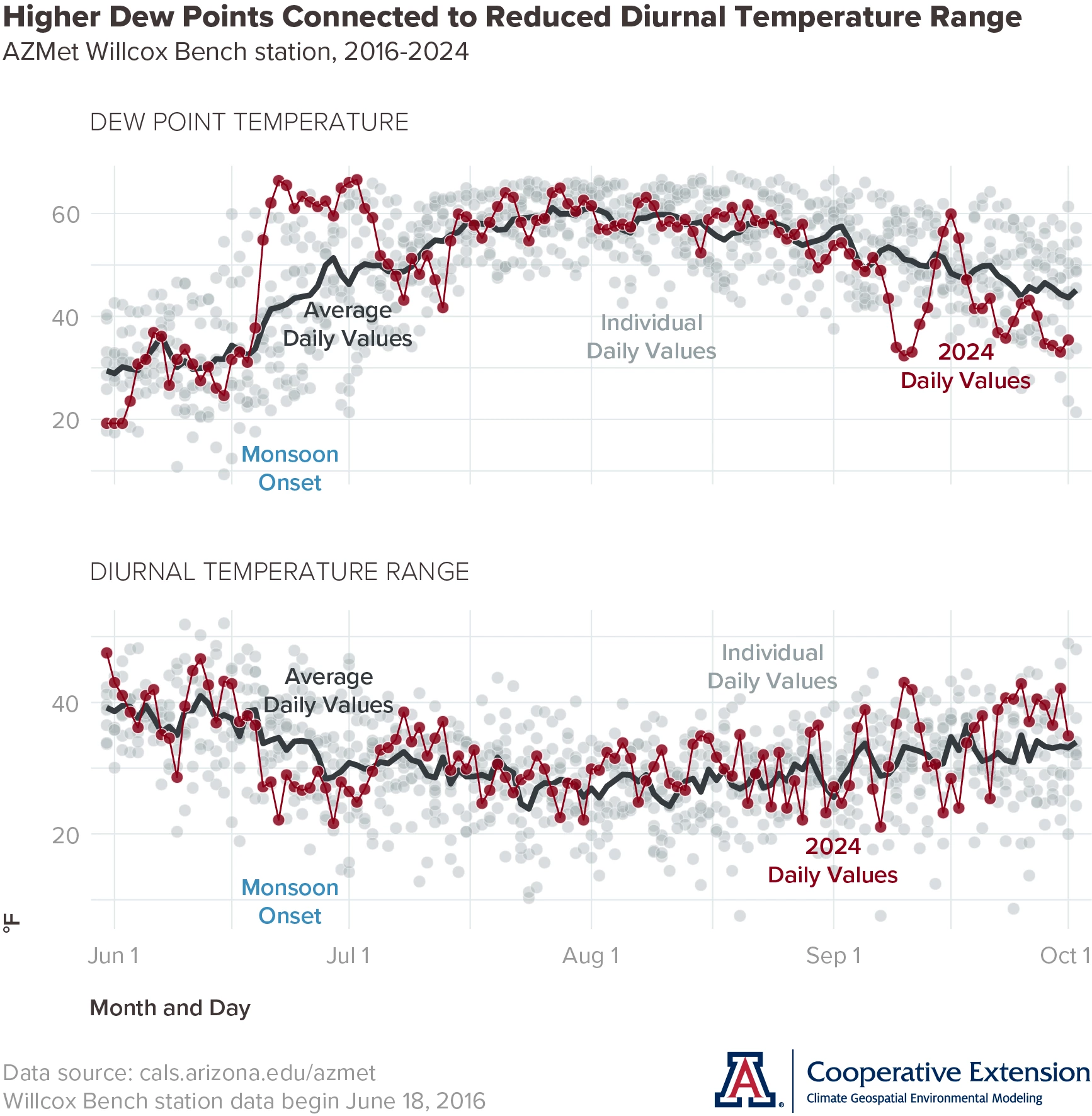

As we all have experienced at some point in late June or early July, a precursor of summer storms arrives in the form of higher humidity. This is evident in dew point temperature data from the AZMet Willcox Bench station in the Willcox AVA (top chart in figure). Average values for a given month and day (dark gray line in top chart) hover near 30 °F for the first part of June. After this, average dew points increase until mid-July, when they level off near 60 °F until mid-August. Average dew points then decline through September, to near 45 °F by the end of that month. Over this four-month period, dew point temperatures for individual days (semi-transparent gray points in top chart) range from near 10 °F in early June to near 70 °F during July and August. Station records begin on June 18, 2016, and we include all available data here.

Average daily values of diurnal temperature range, the difference between maximum and minimum temperatures on a given day, hover between 35 and 40 °F for the first part of June (dark gray line in bottom chart). After this, average diurnal temperature range decreases until mid-July, when it levels off between 25 and 30 °F until late August. It then increases through September, to near 35 °F by the end of that month. Over this four-month period, diurnal temperature range for individual days (semi-transparent gray points in bottom chart) ranges from near 50 °F in mid-June to near 10 °F from late July through September.

Of course, the connection between dew point and diurnal temperature range is not surprising. Higher atmospheric moisture, often accompanied by clouds at this time of the growing season, lowers daily maximum temperatures. This condition also keeps daily minimum temperatures higher, as less heat radiates away from the surface and into the upper levels of the atmosphere during the night. Lower maximum and higher minimum temperatures make for a lower diurnal temperature range.

What stands out to us in the data from 2024 is the sharp increase in dew point temperature during June just past the mid-point of the month, and the corresponding decrease in diurnal temperature range. Those dew point values are among the highest recorded in June at the Willcox Bench station and resulted in below-average diurnal temperature range values. Otherwise for this growing season, dew point temperature and diurnal temperature range hovered near respective averages.

Let’s bring this back to the vineyard. How might higher humidity and lower diurnal temperature range during ripening and harvest affect fruit quality and composition? We look at one possible answer to this in the next section.

Jeremy Weiss

Temperature Ranges and the Ripening Period

Like many other questions, one answer to how higher humidity and lower diurnal temperature range during ripening and harvest affect fruit quality and composition is ‘it depends’. In this case, it depends on how the maximum and minimum temperatures that determine diurnal temperature range relate to temperature thresholds important to vine and fruit physiology and metabolism. As in previous newsletter issues, we focus here on 95 and 65 °F for maximum and minimum temperatures, respectively. The former, for example, relates to the upper temperature limit of photosynthesis as well as effects such as anthocyanin degradation, and the latter to respiration of malic acid and declines in fruit acidity.

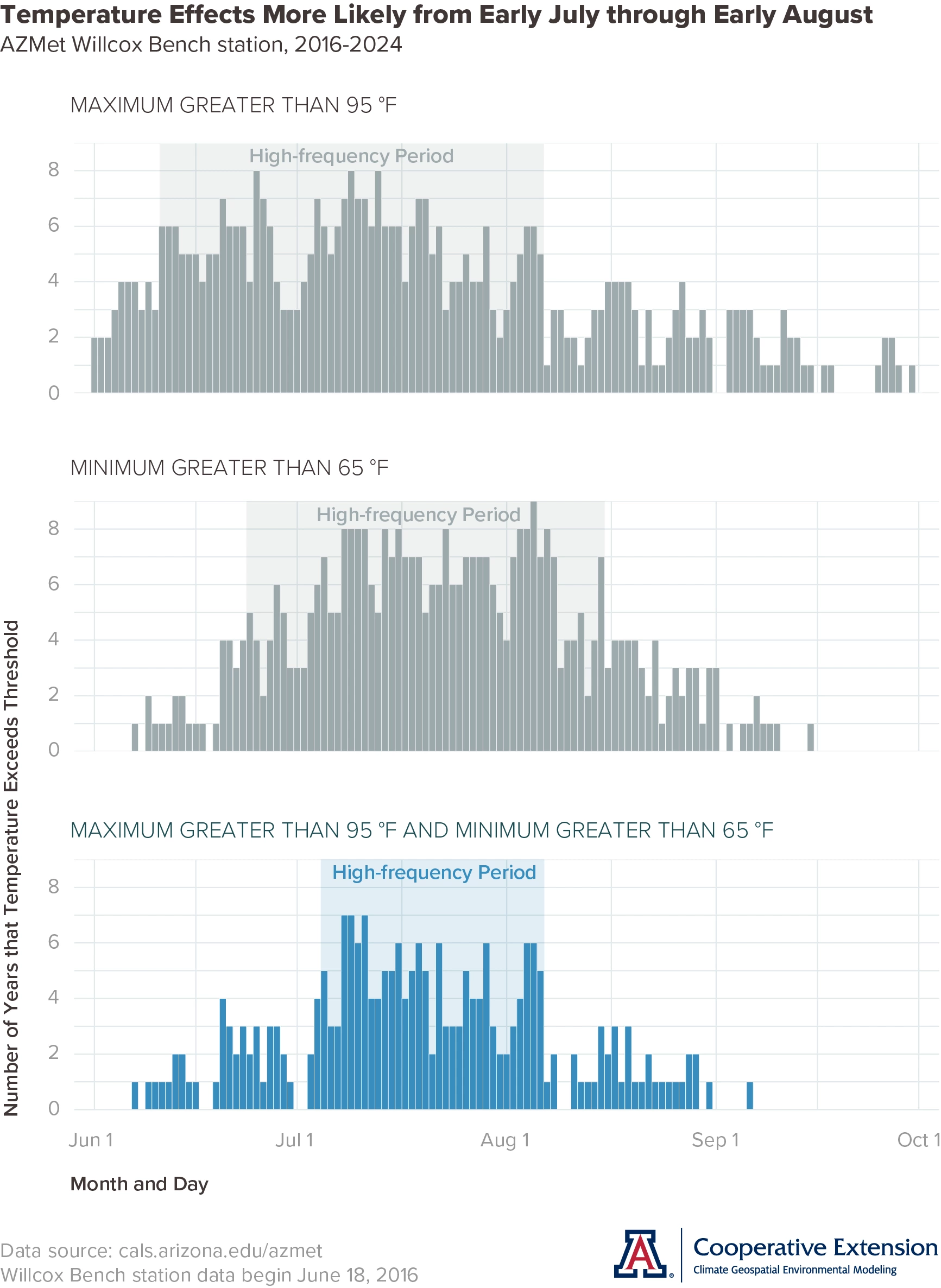

We also again focus here on frequency, how often maximum and minimum temperatures respectively are above these thresholds. What’s new is that we present frequency as a count of how often these conditions occur for a given month and day over the course of the nine-year record from the AZMet Willcox Bench station in the Willcox AVA. Although a longer record would be better when it comes to statistics, patterns of how these conditions vary during the June-through-September period already may be apparent.

Daily maximum temperatures greater than 95 °F occur from early June through late September, and most often from mid-June through early August (gray bars in top chart). During this period of relatively higher frequency, measurements of maximum temperatures above 95 °F for a given month and day happen between two and eight years out of nine, with an average frequency of 5.3 years out of nine or almost 60 % of the time. Prior to and after this high-frequency period, this condition occurs between zero and four years out of nine.

Daily minimum temperatures greater than 65 °F occur from mid-June through mid-September, and most often from late June through mid-August (gray bars in middle chart). During this period of relatively higher frequency, measurements of minimum temperatures above 65 °F for a given month and day happen between three and nine years out of nine, with an average frequency of 5.9 years out of nine or about 65 % of the time. Prior to and after this high-frequency period, this condition occurs between zero and four years out of nine. We’re certain that you already have connected this information to that about dew point temperatures in the previous section.

Combining both thresholds, daily maximum temperatures greater than 95 °F and minimum temperatures greater than 65 °F occur from early June through early September, and most often from early July through early August (blue bars in bottom chart). During this period of relatively higher frequency, measurements of maximum and minimum temperatures above 95 and 65 °F, respectively, for a given month and day happen between two and seven years out of nine, with an average frequency of 4.5 out of nine or about 50 % of the time. Prior to and after this high-frequency period, this condition occurs between zero and four years out of nine.

In addition to how frequency of the individual conditions varies from June through September and despite a relatively short station record, a couple things catch our eye. One is that the high-frequency periods for maximum temperatures greater than 95 °F and minimum temperatures greater than 65 °F do not quite line up. The former looks to start a few weeks earlier than the latter, while both end close to the same time. The other is that the time when there is overlap between these two high-frequency periods (high-frequency period for blue bars in bottom chart) may represent one of the most challenging parts of the ripening and harvest season, as effects of temperature on vine and fruit physiology and metabolism appear to be more numerous and more likely.

Finally, what are the implications from this analysis for monsoon hedging? For us, they include how varieties, whether early maturing or late, and wine styles, like sparkling or dry, line up with the high-frequency periods of the different conditions presented here. Are the grapes in question heat tolerant if they ripen when maximum temperatures above 95 °F are more likely? Can they maintain acidity if they ripen when minimum temperatures above 65 °F are more likely? Characteristics like these are just a few that might help when evaluating varieties for Arizona vineyards.

Jeremy Weiss

Extra Notes

Given recent and current conditions, there is an above-normal potential for significant wildland fires across the central and northwestern parts of Arizona in October. Otherwise across the state, the outlook from the National Interagency Fire Center shows potential as normal for the month.

Although ENSO-neutral conditions – those of neither El Niño nor La Niña, rather long-term average sea-surface temperature, wind, surface pressure, and rainfall across the tropical Pacific Ocean – remain in place, odds are 71 % that La Niña conditions develop during the September-through-November period, with the expectation that they persist through the January-through-March period. This forecast also indicates a weak La Niña event of short duration, which implies that the typical below-normal totals of seasonal precipitation resulting from this ENSO phase may be less likely.

The next viticulture symposium presented by Cooperative Extension will be December 4, 2024 at the University of Arizona Controlled Environment Agriculture Center in Tucson. Topics will include soils and fertility, integrative pest management, pathology, weather and climate, and the industry’s impact on tourism. Continuing education credits will be offered for licensed applicators. Registration details will be available soon.

For those of you in southeastern Arizona, including the Sonoita and Willcox AVAs, Cooperative Extension manages an email listserv in coordination with the Tucson forecast office of the National Weather Service to provide information in the days leading up to agriculturally important events, like heavy rainfall from tropical cyclone remnants and early fall freezes. Please contact us if you'd like to sign up.

And for those of you in north-central and northeastern Arizona, including the Verde Valley AVA, Cooperative Extension also now manages an email listserv in coordination with the Flagstaff forecast office of the National Weather Service to provide similar information for this part of the state. Please contact us if you'd like to sign up.

Undergraduate students in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at the University of Arizona are looking for internships with businesses and companies in the viticulture and winery industries. Please contact Danielle Buhrow, Senior Academic Advisor and Graduate Program Coordinator in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, for more information.

Please feel free to give us feedback on this issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter, suggestions on what to include more or less often, and ideas for new topics.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Please contact us to subscribe.

Have a wonderful October!

With current and past support from: