< Back to Climate Viticulture Newsletter

Hello, everyone!

This is the April 2022 issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter – a quick look at some timely climate topics relevant to wine grape growing in Arizona.

March Recap | April Outlook | AVA Seasonal Analogs | Start of the Growing Season | Extra Notes

A Recap of March Temperature and Precipitation

Monthly average temperatures were within 2 °F of the 1991-2020 normal for much of the state (light green and yellow areas on map). A few areas in the eastern part of Arizona, including the Willcox AVA, were 2 to 4 °F below normal (dark green areas on map). These conditions generally are similar to those in March last year when temperatures were 1 to 3 °F below the 1981-2010 normal for almost all of the state.

NOAA ACIS

Rain and snow last month did little to change the mostly dry storyline of this dormant season. Monthly totals were less than 50 % of the 1991-2020 normal for much of the southern and western halves of the state (red and dark red areas on map). Some areas like the Sonoita and Verde Valley AVAs fared marginally better with precipitation amounts 50 to 100 % of normal (dark orange, orange, and yellow areas on map). Only a few locations managed above-normal amounts from March storms, these mostly along the Mogollon Rim and on the Colorado Plateau in northeastern Arizona. Like temperature, these conditions generally are similar to those during March 2021 when precipitation totals were less than 70 % of the 1981-2010 normal for much of the state, with only some areas in the northern part receiving near-normal amounts.

March likely wasn’t warm enough to make vines rush out of dormancy and into the growing season, like in 2017 for some locations. Nor did it do much to help current drought conditions in Arizona, which are helping set the stage for the current wildland fire season and early-season irrigation needs. More on much of this in following sections.

View more NOAA ACIS climate maps

NOAA ACIS

The Outlook for April Temperature and Precipitation

Temperatures over the course of this month have a moderate increase in chances for being above the 1991-2020 normal across almost all of Arizona (dark orange area on map). This outlook only is different for the extreme northwestern part of the state, where there only is a slight increase in chances for above-normal temperatures (orange area on map). For comparison, monthly temperatures in April last year were 2 to 4 °F above the 1981-2010 normal for almost all of the state.

climate.gov

Precipitation totals for this month have a slight increase in chances for being below the 1991-2020 normal across much of the state (tan area on map). Differing from this is the east-central and southeastern parts of the state, where chances for below-normal amounts are moderate (brown area on map). Precipitation during April 2021 was less than 50 % of the 1981-2010 normal for most of Arizona.

With the April outlook leaning towards warmer and drier than normal, the first part of the growing season is leaning towards looking like last year, both in terms of timing of and between phenological stages and vineyard irrigation needs. But first thing – bud break – first. More on the start of the growing season below.

Read more about the April 2022 temperature and precipitation outlook

To stay informed of long-range temperature and precipitation possibilities beyond the coverage of a standard weather forecast, check in, too, with the six-to-ten-day outlook and eight-to-fourteen-day outlook issued daily by NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

climate.gov

Seasonal Analogs for Arizona AVAs

With March data in, we close out our ‘analog’ analysis for the 2021-2022 dormant season. For the Sonoita AVA (top graph), temperature and precipitation since November are most similar to that from winters 1999-2000, 2015-2016, 1981-1982, 2020-2021, and 2005-2006. The first two winters in that list also are in the list for the Verde Valley AVA (middle graph), along with 2013-2014, 1983-1984, and 2003-2004. For the Willcox AVA (bottom graph), winters 2001-2002, 2020-2021, 1988-1989, 2012-2013, and 2002-2003 are most similar.

Throughout this dormant season, conditions consistently were warmer and drier than the 1991-2020 normals (thick gray lines in all graphs) for the Sonoita and Verde Valley AVAs. Below-normal precipitation during the past five months also characterized the Willcox AVA, but in a bit of contrast, below-normal temperatures in February and March brought the seasonal value closer to this climatological marker. Average temperatures for the three AVAs from November through March were between 49 and 50 °F and precipitation totals between 2 and 4 inches.

These conditions likely resulted in keeping close attention on dormant-season irrigation for a few reasons like leaching of root-zone salts and getting more control over the first part of the growing season. Low soil moisture can delay or reduce bud rehydration, swelling, and weeping, as well as push back budbreak dates and predispose vines to delayed spring growth.

If your vineyard is in or near the state AVAs, use the corresponding list of years above to help filter your field notes and zero in on past observations that could be more useful in planning activities at this point in this growing season.

Jeremy Weiss

Vine Dormancy and the Start of the Growing Season

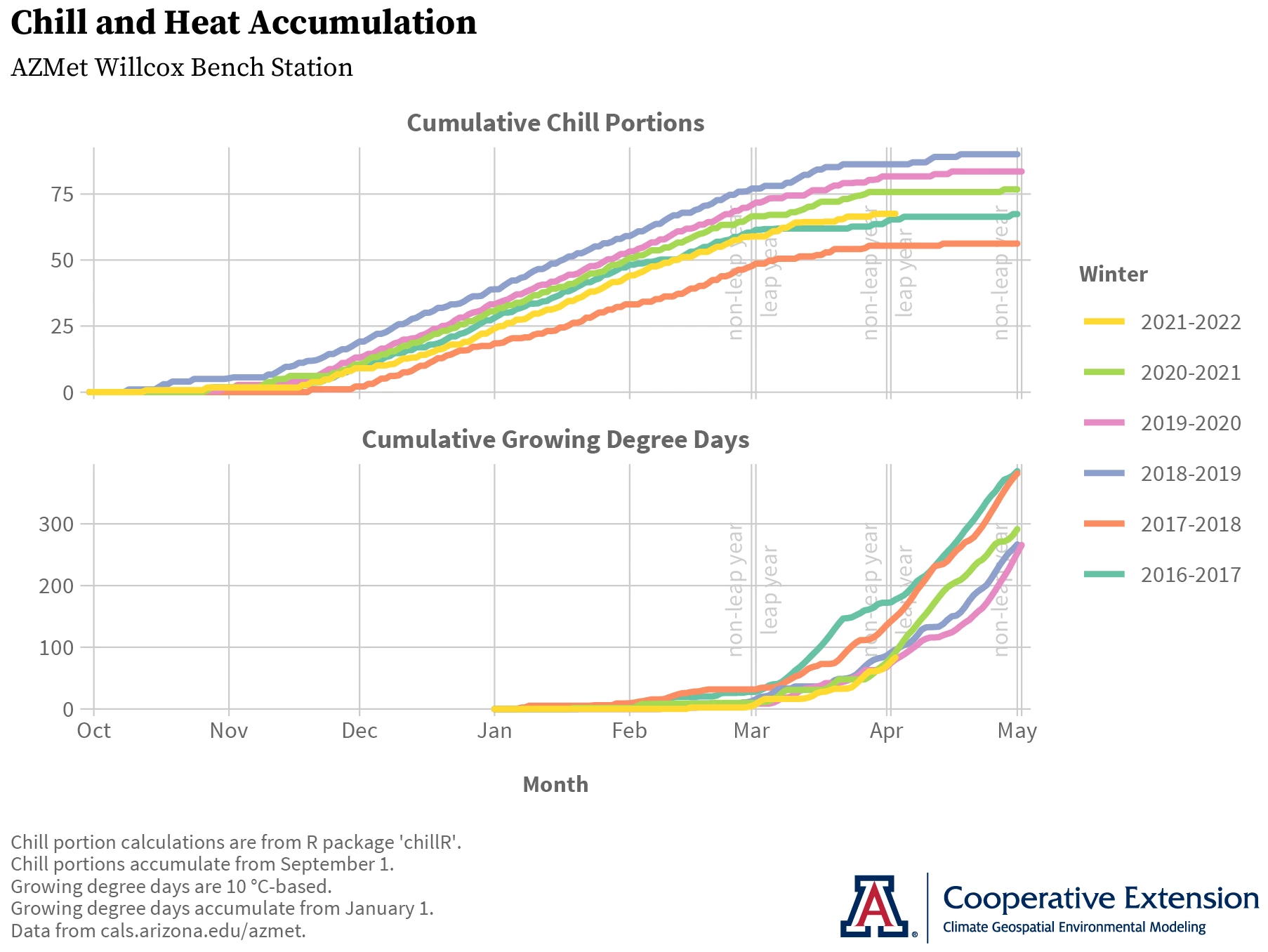

Along with low soil moisture, another factor that could play a role in determining bud break dates this year is lower chill accumulation relative to the past three. Due to deacclimation kinetics, less chill can translate to a slightly lower rate at which dormant buds deacclimate and a slightly longer time over which they lose cold hardiness. Although we don’t know the exact roles these two factors are playing in 2022, the latter has been leading us to expect a relatively late start to the growing season, at least near the AZMet Willcox Bench station in the south-central part of the Willcox AVA.

Here’s why. Temperature conditions there so far this dormant season continue to result in cumulative chill portion values that are most similar to those from winter 2016-2017 (yellow and aqua lines in top graph, respectively). But, cumulative growing degree day values continue to be most like those from winters 2020-2021, 2019-2020, and 2018-2019 (yellow, green, pink, and blue lines in bottom graph, respectively). Without a singular past year matching 2022 for both chill and heat accumulation, an ‘analog’ approach won’t work well. What might is the aspect of deacclimation kinetics that explains why relatively higher (lower) heat accumulation is needed for vines to start the growing season after winters with relatively lower (higher) chill accumulation.

So with current chill accumulation at relatively lower values than the past three years, our educated guess still is that a relatively higher amount of heat accumulation than the past three years is needed for budbreak in 2022. As heat accumulation this year continues to track that of the past three (yellow line and green, pink, and blue lines in bottom graph, respectively), a relatively late start to the growing season still looks be in the works, at least at this location.

To continue tracking chill and heat accumulation during the month, visit our related early-stage, interactive web application that updates daily. And if you haven’t already, please reach out and let us know how bud break timing is in your vineyard this year.

Jeremy Weiss

Although expected to continue dissipating, the ‘double-dip’ La Niña event of this dormant season continues to persist, albeit weakly. There is a 53 % chance of ENSO conditions transitioning to neutral between May and July. This is the most recent official forecast for ENSO, or El Niño Southern Oscillation, parts of the atmosphere and ocean across the tropical Pacific Ocean that cause El Niño and La Niña events.

It’s no surprise that drought conditions already are influencing the wildland fire season in the state. There is an above-normal potential this month for significant wildland fires in southeastern and central Arizona. Elsewhere across the state, the potential is normal.

Besides the start of the growing season, late March and early April also bring the climatological last spring freeze to warm-climate growing areas in the region. For those of you in southeastern Arizona, Cooperative Extension manages an email listserv in coordination with the Tucson forecast office of the National Weather Service to provide information in the days leading up to such agriculturally important events. Please contact us if you'd like to sign up.

And for those of you in north-central and northeastern Arizona, Cooperative Extension is starting to coordinate with the Flagstaff forecast office of the National Weather Service to soon provide a similar email listserv for those in agriculture in this part of the state. Please contact us if you'd like to sign up.

Undergraduate students in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at the University of Arizona are looking for internships with businesses and companies in the viticulture and winery industries during 2022. Please contact Danielle Buhrow, Senior Academic Advisor and Graduate Program Coordinator in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, for more information.

Please feel free to give us feedback on this issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter, suggestions on what to include more or less often, and ideas for new topics.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Please contact us to subscribe.

Have a wonderful April!

With current and past support from: