< Back to Climate Viticulture Newsletter

Hello, everyone!

This is the February 2021 issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter – a quick look at some timely climate topics relevant to winegrape growing in Arizona and New Mexico.

A Recap of January Temperature and Precipitation

Average temperatures last month were within 2°F of the 1981-2010 normal for almost all of the region (light green and yellow areas on map). A few locations recorded temperatures 2°F to 4°F below normal (dark green areas on map). These conditions are largely similar to those of January last year, when temperatures were within 2°F of normal for most of the region, except for northern Arizona and northern and eastern New Mexico where they were 2°F to 4°F above normal.

NOAA ACIS

Some areas in central and southern Arizona and extreme west-central, north-central, and southeastern New Mexico enjoyed a slight reprieve from the anticipated dry winter conditions, with monthly precipitation totals last month over 150% of the 1981-2010 normal (blue and purple areas on map). Otherwise, much of the rest of the region continued with below-normal rain and snow amounts due at least in part to the current La Niña event (orange and red areas on map). For comparison, monthly precipitation totals in January 2020 were below the 1981-2010 normal for almost the entire region.

Despite some storms in January, precipitation totals for the past three months – roughly the period of vine dormancy so far this year – remain below average for several growing areas in the region. For reference, the 1981-2010 normal for November through January precipitation tells us to expect about two to four inches at each of the six AVAs in Arizona and New Mexico. Factoring in temperature over this same period, which has been above normal for several growing areas, suggests that the precipitation we did see will be less effective in increasing soil moisture as higher temperatures increase evaporation. This is particularly the case for vineyards in relatively warmer winegrape growing areas. Closer attention to irrigation and soil moisture this winter relative to the past two still seems to be necessary to help guard against damage from cold temperatures as well as delayed spring growth.

NOAA ACIS

The Outlook for February Temperature and Precipitation

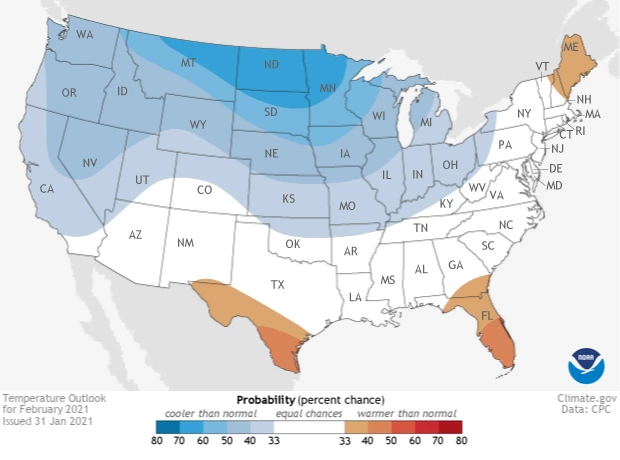

There are equal chances for below-, near-, or above-normal temperatures for almost the entire region (white area on map). A slight increase in chances for below-normal temperatures exists for extreme northwestern Arizona (light blue area on map), whereas a slight increase in chances for above-normal temperatures exists for extreme southern New Mexico (light orange area on map). As a comparison, temperatures in February last year were within 2° Fahrenheit of the 1981-2010 normal across much of the region.

climate.gov

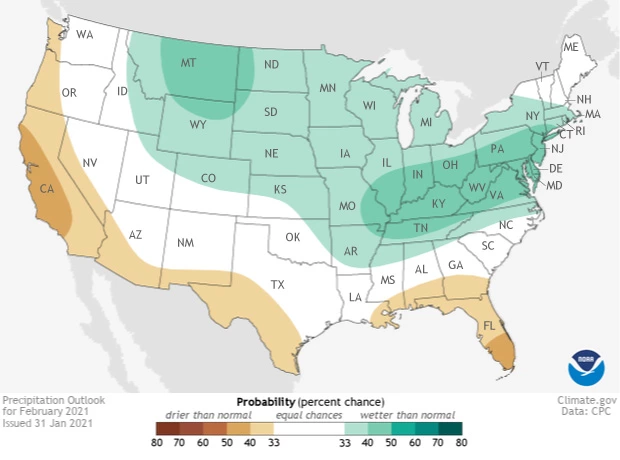

A slight increase in chances for below-normal precipitation exists for western and southern Arizona as well as southern New Mexico (light tan area on map). Equal chances for below-, near-, or above-normal precipitation exist for the rest of the region (white areas on map). Monthly precipitation totals in February 2020 were above the 1981-2010 normal over an area stretching from southwestern Arizona to central New Mexico, whereas below-average amounts fell over much of northern Arizona and extreme northern and eastern New Mexico.

How temperature and precipitation play out over the coming month will have a role in determining the start of the growing season. As we start the month, cumulative chill portions based on data from the Arizona Meteorological (AZMET) Network Willcox Bench station are most similar to those in winter 2016-2017. Although cumulative growing degree days are most similar to those of the past two winters, there is not a lot of difference between any of the values so early in the year and this makes it difficult to see if current chill and heat accumulations are analogous to any previous growing seasons. We’ll be paying much closer attention to this topic in the coming weeks.

climate.gov

Climate Change and Viticulture: Late-dormancy Precipitation

Since a general lack of rain and snow for many areas likely will be the main climate-and-viticulture talking point from this winter, our focus this month for this topical series is on precipitation during the latter half of vine dormancy. The Sonoita, Willcox, and proposed Verde Valley AVAs once again serve as examples.

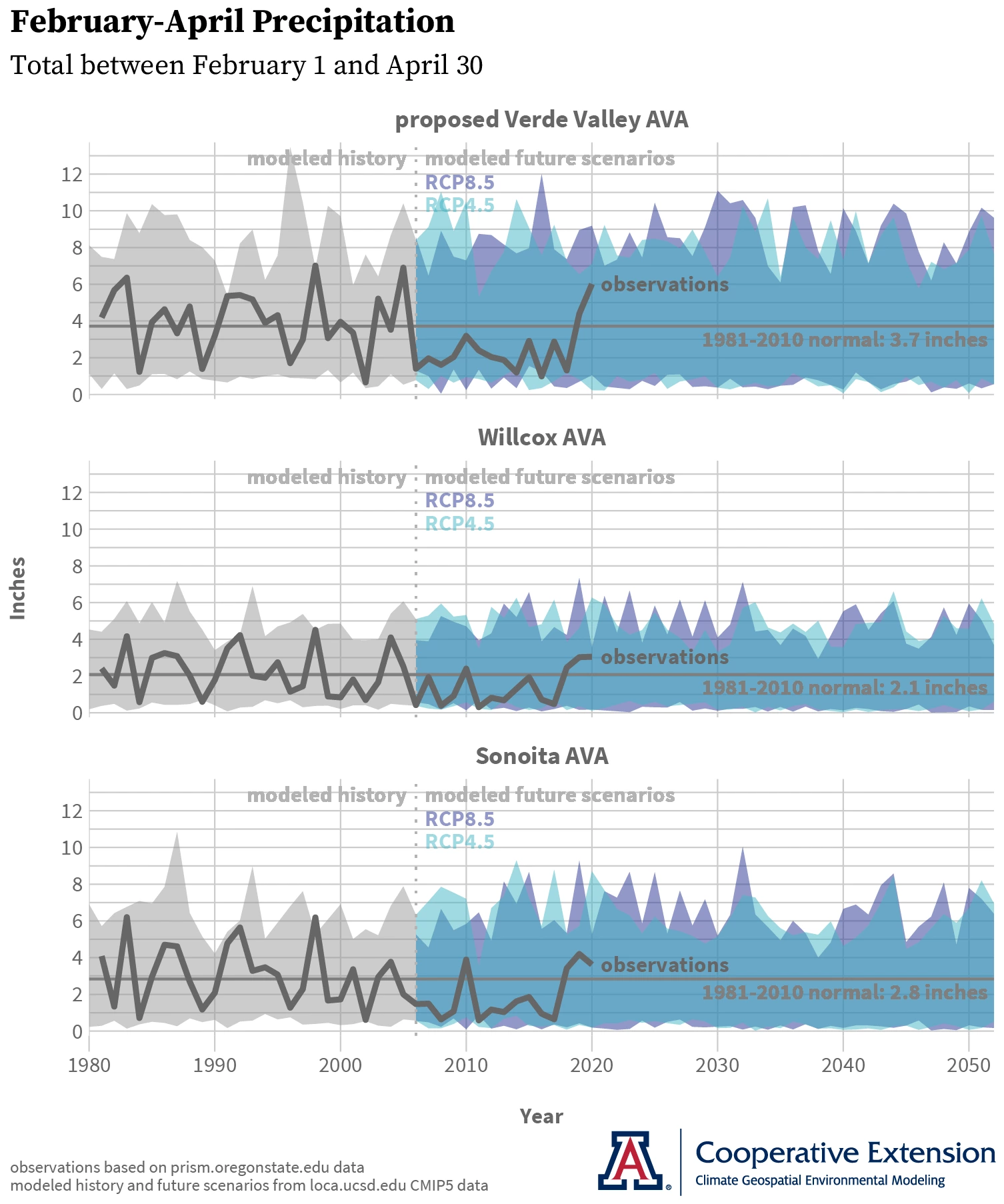

We’ve plotted the historical observations and 1981-2010 normals of total precipitation between February 1 and April 30 (thick dark gray and gray lines, respectively). These data overlay the range of total precipitation as estimated for these areas by 32 models used to project plausible future climatic conditions. Observations for all three AVAs lie almost entirely within the ‘modeled history’ (gray shading), indicating that the models do well in representing past rain and snow amounts during this time of the year. Observations continue to occur within the band of ‘modeled future scenarios’ through 2020 (aqua, blue, and purple shading1). We can expect total February-April precipitation to remain similar over the next 30 years, such that year-to-year variations and values both above and below the 1981-2010 normals continue to occur.

The expectation for near-normal or relatively wet or dry conditions leading up to the start of the growing season points to the effect that global climate phenomena, like the La Niña event this winter, will continue to have on the region in the coming decades. One concern that has long troubled the Southwest in this context is when dry years happen in succession or more frequently over several years – something we experienced during the 2000s and 2010s – and lead to long-term drought and consequent impacts like reduced water resources. Another, more recent concern is the effect that continued regional warming will have on the precipitation we do get. As noted above, one thing warmer temperatures can lead to is increased evaporation, which in turn decreases soil moisture more quickly. For the months of February, March, and April, this could be an issue closer to the start of the growing season, when temperatures typically are higher. It is much easier to imagine this being an issue later in the growing season, when higher rates of both evaporation and transpiration would be expected under above-normal temperatures. Although the amount of irrigation needed for a vineyard may thus increase in the coming years due to further changes in climate, adaptations like increasing soil water-holding capacity and using drought-resistant rootstocks can help minimize this demand.

1 ‘Modeled future scenarios’ are based on two different pathways of future greenhouse-gas emissions. RCP4.5 (aqua shading) corresponds to a relatively slower increase of carbon emissions to 2050, relative to RCP8.5 (purple shading). Blue shading represents the overlap of ranges of total February-April precipitation based on the scenarios. Global climate models use these scenarios to drive plausible trajectories of future climatic conditions. RCP is an abbreviation for Representative Concentration Pathway.

Jeremy Weiss

La Niña conditions persisted over the past month and current forecasts still show a 95% chance that this event will last through March before likely dissipating thereafter. With current forecasts, dry conditions in the region over the coming months are more likely but not heavily favored.

A recent donation of 40 acres near Willcox plus recent funding from the USDA-AZDA Specialty Crop Block Grant program are some of the first steps of a newly formed public-private collaboration towards a Viticulture Center of Research (VCOR) that will help support winegrape growing in Arizona. The funding will provide resources to convene the state viticulture industry and its supporters in the latter half of 2021 to determine common interests and develop plans for moving the VCOR project forward. Another first step is to gather letters of support that demonstrate backing of the VCOR project from the Arizona viticulture industry to relevant leaders in the University of Arizona. To learn more about the VCOR project and how to contribute a letter of support, please contact Joshua Sherman, commercial horticulture agent with University of Arizona Cooperative Extension.

Undergraduate students in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at the University of Arizona are looking for internships with businesses and companies in the viticulture and winery industries during 2021. Please contact Danielle Buhrow, Senior Academic Advisor and Graduate Program Coordinator in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, for more information.

For those of you in southeastern Arizona, Cooperative Extension manages an email listserv in coordination with the Tucson forecast office of the National Weather Service to provide information in the days leading up to agriculturally important events, like winter storms and cold-air outbreaks. Please contact us if you'd like to sign up.

Please feel free to give us feedback on this issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter, suggestions on what to include more or less often, and ideas for new topics.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Please contact us to subscribe.

Have a wonderful February!

With support from: