< Back to Climate Viticulture Newsletter

Hello, everyone!

This is the April 2021 issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter – a quick look at some timely climate topics relevant to winegrape growing in Arizona and New Mexico.

A Recap of March Temperature and Precipitation

Average temperatures last month were 1 to 3 °F below the 1981-2010 normal for most of Arizona (dark green and blue areas on map). Conditions generally were warmer as one went east, with temperatures near normal for much of New Mexico (light green and yellow areas on map). A broadly similar pattern occurred in March last year, with temperatures near or up to 5 °F cooler than normal for much of Arizona, and near or up to 5 °F warmer than normal for much of New Mexico.

NOAA ACIS

For the most part, March maintained the drought conditions in the region. Monthly totals less than 70% of the 1981-2010 normal (dark orange and red areas on map) covered much of Arizona and New Mexico, especially across the southern half of each state. A few areas scattered across the northern tier of the region received near- to above-normal amounts (yellow, green, blue, and purple areas on map). These conditions contrast with what we experienced in March 2020, when monthly precipitation totals were near- or above-normal across much of the region, except for northeastern New Mexico.

In general, temperatures last month continued to kept chill and heat accumulation – and their influences on the timing of budbreak – similar to that of the past two years. We’ll dig more into this below. For precipitation, the relative lack of rain and snow during March – and during the past several months – may be a contributing factor to higher soil salinity levels, as recent amounts likely have not been enough to help flush salts past upper root zones. This could be a particular issue if the groundwater used for irrigation is saline. The recent lack of precipitation also may be contributing to lower soil moisture levels that, based on some recent experimental evidence, can delay or reduce bud rehydration, swelling, and weeping, as well as push back budbreak dates.

View more NOAA ACIS climate maps

NOAA ACIS

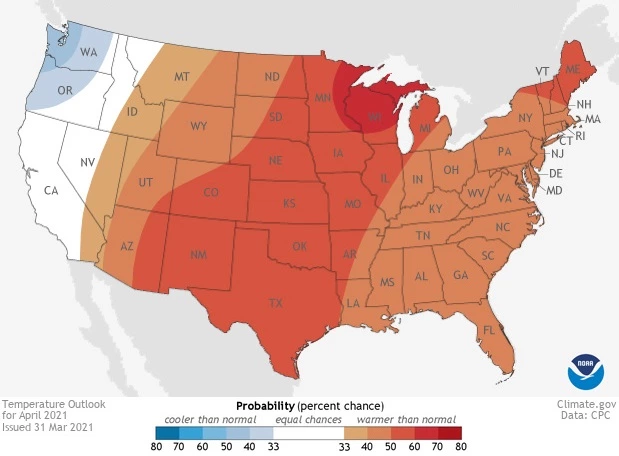

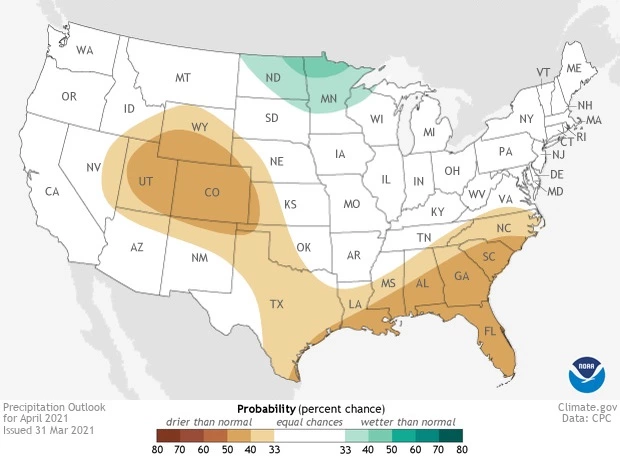

The Outlook for April Temperature and Precipitation

Slight chances for above-normal temperatures exist for the western half of Arizona (orange and light orange areas on map), whereas moderate chances exist for above-normal temperatures over the eastern half of the state and all of New Mexico (dark orange area on map). Looking back to April last year, temperatures were near or up to 3 °F warmer than normal for almost all of the region.

climate.gov

A slight increase in chances for below-normal precipitation exists across northern Arizona and northern New Mexico (light and dark tan areas on map). Equal chances for below-, near-, or above-normal precipitation exist for the rest of the region (white area on map). Monthly precipitation totals in April 2020 were below normal for much of the region.

If temperatures turn out to be above normal this month, as currently favored and as they largely were in April 2020, we can anticipate that the rate of shoot development and time between early-season growth stages will be like that of last year. Such a vineyard outlook might be more relevant to warmer growing areas where budbreak occurs earlier in the year, rather than to cooler ones where chill and heat accumulations remain the main temperature-related topic over the next few weeks. The main precipitation topic also is in transition, as the current La Niña event is in its final stages and we turn our attention to the summer monsoon. Outlooks for the latter are coming soon.

Read more about the April 2021 temperature and precipitation outlook

climate.gov

Vine Dormancy and the Start of the Growing Season

As noted above, the song remained about the same over the past month. Values of both cumulative chill portions and cumulative growing degree days continue to closely track those observed during the past two years, winters 2019-2020 and 2018-2019, at the AZMET Willcox Bench station in the south-central part of the Willcox AVA (green, pink, and blue lines on graphs). Based on degree-day calculations from the National Phenology Network, heat accumulations for other warm-climate growing areas in the region also appear similar to those from this time last year.

Using winters 2019-2020 and 2018-2019 as ‘analogs’, expectations for the timing of budbreak this year have been pointing so far to dates similar to those of the past two. All else equal, however, there are a couple factors that might make budbreak dates slightly later this year. One is relatively lower soil moisture levels, something we noted above. The other is slightly less chill accumulation this year, something we look at in the next section.

Jeremy Weiss

What We're Reading

Deacclimation kinetics. Say what?! That was our reaction when starting to read a recent article in AoB PLANTS by Kovaleski and colleagues that demonstrates how chill accumulation, dormancy state, and temperature affect the loss of cold hardiness and timing of budbreak in grapevines. Their conclusion essentially boils down to this: The same above-freezing temperature at different times during dormancy may not have the same effect in advancing a vine towards budbreak. It depends on the coincident dormancy state and chill accumulation. Their findings provide an explanation for observations of budbreak occurring at lower growing degree day but higher chill accumulations.

During vine dormancy, cold hardiness progresses through the stages of acclimation, maintenance, and deacclimation. Acclimation, the progressive gain of cold hardiness, primarily occurs during endodormancy, whereas deacclimation, the progressive loss of cold hardiness, becomes more prominent during ectodormancy. Vines likely change from endo- to ectodormancy towards the end of acclimation or during the maintenance stage. The transition from endo- to ectodormancy represents when there has been sufficient exposure of dormant buds to low, non-freezing temperatures, or in other words, when the chilling requirement has been met. Budbreak takes place when cold hardiness is lost.

As evident in the graph from the previous section, chill does not accumulate the same every year. These differences not only vary the date when chilling requirements are met, but also vary the rate at which deacclimation occurs. The greater the chill accumulation, the faster that dormant buds deacclimate at a given temperature. Kovaleski and colleagues refer to this effect of chill on deacclimation rate as deacclimation potential.

Their study also reveals that, at a given chill amount and temperature, varieties can differ in how efficiently they use heat to deacclimate. Based on their observations, for example, deacclimation rates for Vitis vinifera ‘Riesling’ are greater than those of V. vinifera ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’. An important consequence here is that different deacclimation rates influence how quickly cold hardiness is lost and thus when budbreak occurs. As you might expect, the authors also observed an earlier budbreak for ‘Riesling’ than for ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’. One can generalize these results by regarding early, intermediate, and late budbreak varieties as having progressively lower deacclimation rates. Perhaps most intriguing is that once the differences in deacclimation rates are accounted for, both ‘Riesling’ and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ show the same amount of growing degree days needed to reach budbreak.

Let’s now bring deacclimation kinetics to the Southwest. Using budbreak data provided by Jesse Noble at Merkin Vineyards, the previously mentioned pattern of ‘higher chill-lower growing degree days’ is clear (top graph). For winters 2016-2017 and 2017-2018 at the nearby AZMET Willcox Bench station, cumulative chill portions on budbreak dates range between 50 and the lower 60s while cumulative growing degree days are mostly between 150 and 250 (teal and orange dots, respectively). For winters 2018-2019 and 2019-2020, chill portions hover near 80 whereas degree days mostly range between 100 and 150.

Another previously mentioned pattern appears when we look at these data through a variety lens. Budbreak dates for ‘Riesling’ are earlier than those of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’. This is represented in the lower graph by consistently lower accumulations of growing degree days for ‘Riesling’ (dark yellow dots) than for ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ (dark purple dots) during individual winters. By directly seeing these two patterns, there’s a good chance we also are indirectly seeing the differing deacclimation rates described above at work here in our neck of the woods.

We’ll conclude for now on this topic with two points. First, adding the science from the Kovaleski and colleagues study to the current conditions of having slightly less chill accumulation opens the possibility for later budbreak dates this year relative to the past two due to lower deacclimation rates. Second, the ‘analogs’ approach with chill and heat accumulation in the previous section should serve us well in predicting the start of the growing season until we assemble a larger budbreak database from which to develop more robust, variety-specific models. Such models can be useful for near-term planning of vineyard activities, as well as for anticipating long-term changes in growth-stage timing from further increases in seasonal temperatures that can alter spring freeze risk and the conditions under which fruit ripens.

Jeremy Weiss

Another impact of the drought conditions over recent months is a quick start to the fire season. There is an above-normal potential this month for significant wildland fires for areas in Arizona south and west of the Mogollon Rim and for southern and eastern New Mexico. Although smoke taint certainly is not a threat to winegrapes in the Southwest during April, here’s an easy read on recent UC Davis work on the topic.

Besides the start of the growing season, late March and early April also bring the climatological last spring freeze to warm-climate growing areas in the region. For those of you in southeastern Arizona, Cooperative Extension manages an email listserv in coordination with the Tucson forecast office of the National Weather Service to provide information in the days leading up to such agriculturally important events. Please contact us if you'd like to sign up.

A recent donation of 40 acres near Willcox plus recent funding from the USDA-AZDA Specialty Crop Block Grant program are some of the first steps of a newly formed public-private collaboration towards a Viticulture Center of Research (VCOR) that will help support winegrape growing in Arizona. The funding will provide resources to convene the state viticulture industry and its supporters in the latter half of 2021 to determine common interests and develop plans for moving the VCOR project forward. Another first step is to gather letters of support that demonstrate backing of the VCOR project from the Arizona viticulture industry to relevant leaders in the University of Arizona. To learn more about the VCOR project and how to contribute a letter of support, please contact Joshua Sherman, commercial horticulture agent with University of Arizona Cooperative Extension.

Undergraduate students in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at the University of Arizona are looking for internships with businesses and companies in the viticulture and winery industries during 2021. Please contact Danielle Buhrow, Senior Academic Advisor and Graduate Program Coordinator in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, for more information.

Please feel free to give us feedback on this issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter, suggestions on what to include more or less often, and ideas for new topics.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Please contact us to subscribe.

Have a wonderful April!

With support from: