< Back to Climate Viticulture Newsletter

Hello, everyone!

This is the 2020 December issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter – a quick look at some timely climate topics relevant to winegrape growing in Arizona and New Mexico.

A Recap of November Temperature and Precipitation

Average temperatures last month were 2°F to 6°F warmer than the 1981-2010 normal for almost all of the region (orange areas on map). For comparison, temperatures in November 2019 were within 2°F of normal for much of the region, except for southern Arizona where temperatures were 2°F to 4°F above normal.

NOAA ACIS

Monthly precipitation totals last month were less than 50% of normal for almost all of the region (red areas on map). In stark contrast, rain and snow amounts last year were above 200% of normal for many areas, as several storms passed through the region.

For many parts of the region like north-central and southeastern Arizona, fall 2020 ranked as one of the warmest and driest on record. After a record-setting hot and dry summer, conditions this autumn wouldn’t let us shake water stress and soil salinity issues – due to relatively high evaporation – from the fronts of our minds. Both can affect fruit composition, with effects of the latter dependent on choices in rootstock and scion, as well as irrigation water quality.

NOAA ACIS

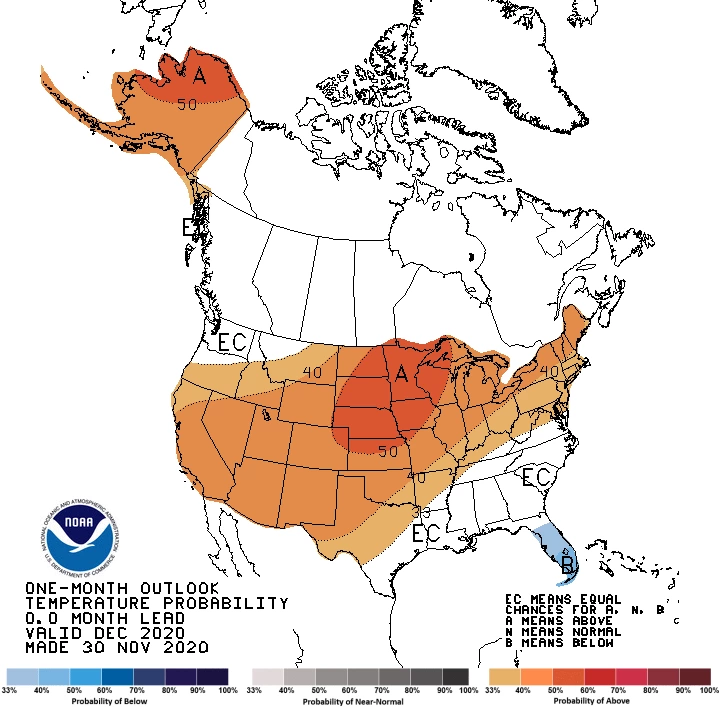

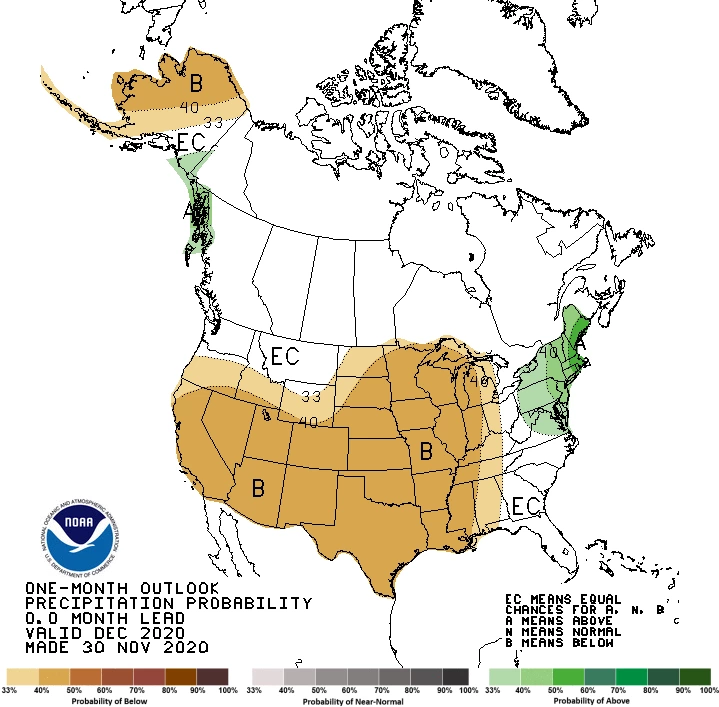

The Outlook for December Temperature and Precipitation

There is a slight increase in chances for above-normal temperatures across all of Arizona and New Mexico (orange area on map). As a comparison, temperatures in December last year were within 2°F of normal for much of the region, except for eastern New Mexico where temperatures were 2°F to 6°F above normal.

NOAA CPC

A slight increase in chances for below-normal precipitation exists for the region (tan area on map). Monthly precipitation totals in December 2019 were above the 1981-2010 normal for most of Arizona and the northern tier of New Mexico, while less than 50% of normal for the rest of the Land of Enchantment.

With an elevated potential for warm and dry conditions to continue, due in part to the ongoing La Niña event, soil moisture in the vineyard may need closer attention this winter relative to the past two. Adequate levels will help guard against damage from cold temperatures as well as delayed spring growth, which manifests as uneven bud break, stunted growth, reduced flower clusters, and other issues.

NOAA CPC

Climate Change and Viticulture: Growing Season Temperature

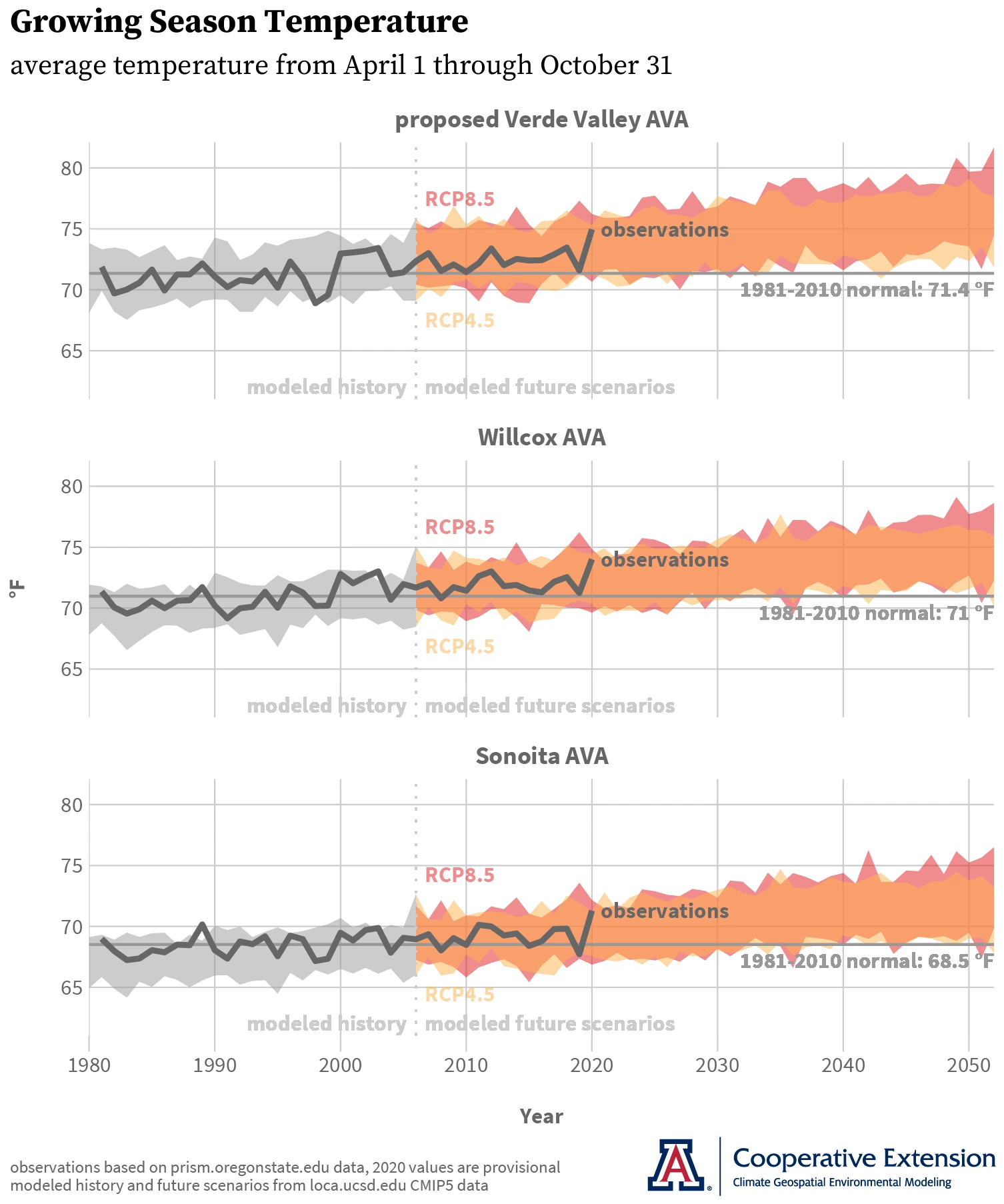

Based on your expressed interest, we’re beginning a new topical series this month that provides information on climate change and viticulture for the region. Up first is growing season temperature, the average temperature between April 1 and October 31. We looked last month at this simple measure, which is used to compare different winegrape growing regions and as a first guess of which grape varieties might do well in a new area, over the past four decades. Now, we’ll look at it over the coming three.

Once again using the Sonoita, Willcox, and proposed Verde Valley AVAs as examples, we’ve replotted from the figure last month the historical observations and 1981-2010 normals (thick dark gray and gray lines, respectively). These data overlay the range of growing season temperatures as estimated for these areas by 32 models used to project plausible future climatic conditions. Observations for all three AVAs lie almost entirely within the ‘modeled history’ (gray shading), which indicates that the models do well in representing past growing season temperatures. Observations continue to occur within the range of ‘modeled future scenarios’ through 2020 (yellow, orange, and red shading1). We can expect growing season temperatures to continue over the next 30 years along the evident warming trend, such that values close to the 1981-2010 normals become unlikely during the 2030s and 2040s while values similar to and warmer than this past year become more likely.

For vineyard decisions that are long term in nature2, such as site selection, row orientation and trellis design, rootstock and scion varieties, and irrigation capacity, climate information – both historical and projected future – plays a particularly important role. Knowing how climatic conditions are likely to change relative to past years can help one determine if and when changes from past long-term decisions – whether from one’s own vineyard or others in the same area that are serving as examples – are needed. This look at growing season temperature gets us started in developing that knowledge, something we’ll continue to do in coming newsletter issues in the context of some of the myriad effects that temperature has on vine growth and fruit quality and composition.

1 ‘Modeled future scenarios’ are based on two different scenarios of future greenhouse-gas emissions. RCP4.5 (yellow shading) corresponds to a slower increase of global carbon emissions to 2050, relative to RCP8.5 (red shading). Global climate models use these scenarios to drive plausible trajectories of future climatic conditions. Orange shading represents the overlap of the ranges of growing season temperature based on the scenarios. RCP is an abbreviation for Representative Concentration Pathway.

2 For a diagram of vineyard management considerations listed by long-term, between-season, and within-season timeframes, see Figure 12 by Webb and colleagues.

Jeremy Weiss

Given the current situation regarding COVID-19, we currently are postponing the Growing Season in Review workshops for 2020. That said, please contact us to schedule a call or virtual meeting if we can be of help as you fill in the climate details for your notes from the vintage this year.

La Niña conditions strengthened over the past month and current forecasts show a 95% chance that this event will persist through the winter. A few forecast models continue to suggest that a strong event is even possible. With current forecasts, dry conditions in the region over the coming months are more likely but not heavily favored.

A recent donation of 40 acres near Willcox plus recent funding from the USDA-AZDA Specialty Crop Block Grant program are some of the first steps of a newly formed public-private collaboration towards a Viticulture Center of Research (VCOR) that will help support winegrape growing in Arizona. The funding will provide resources to convene the state viticulture industry and its supporters in the latter half of 2021 to determine common interests and develop plans for moving the VCOR project forward. Another first step is to gather letters of support that demonstrate backing of the VCOR project from the Arizona viticulture industry to relevant leaders in the University of Arizona. To learn more about the VCOR project and how to contribute a letter of support, please contact Joshua Sherman, commercial horticulture agent with University of Arizona Cooperative Extension.

Undergraduate students in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at the University of Arizona are looking for internships with businesses and companies in the viticulture and winery industry during 2021. Please contact Danielle Buhrow, Senior Academic Advisor and Graduate Program Coordinator in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, for more information.

For those of you in southeastern Arizona, Cooperative Extension manages an email listserv in coordination with the Tucson forecast office of the National Weather Service to provide information in the days leading up to agriculturally important events, like winter storms and cold-air outbreaks. Please contact us if you'd like to sign up.

Please feel free to give us feedback on this issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter, suggestions on what to include more or less often, and ideas for new topics.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Please contact us to subscribe.

We thank all of you for supporting our climate-viticulture project this past year, and we look forward to continuing it in 2021. Have a wonderful December and holiday season!

With support from: