< Back to Climate Viticulture Newsletter

Hello, everyone!

This is the 2019 December issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter – a quick look at some timely climate topics relevant to winegrape growing in Arizona and New Mexico.

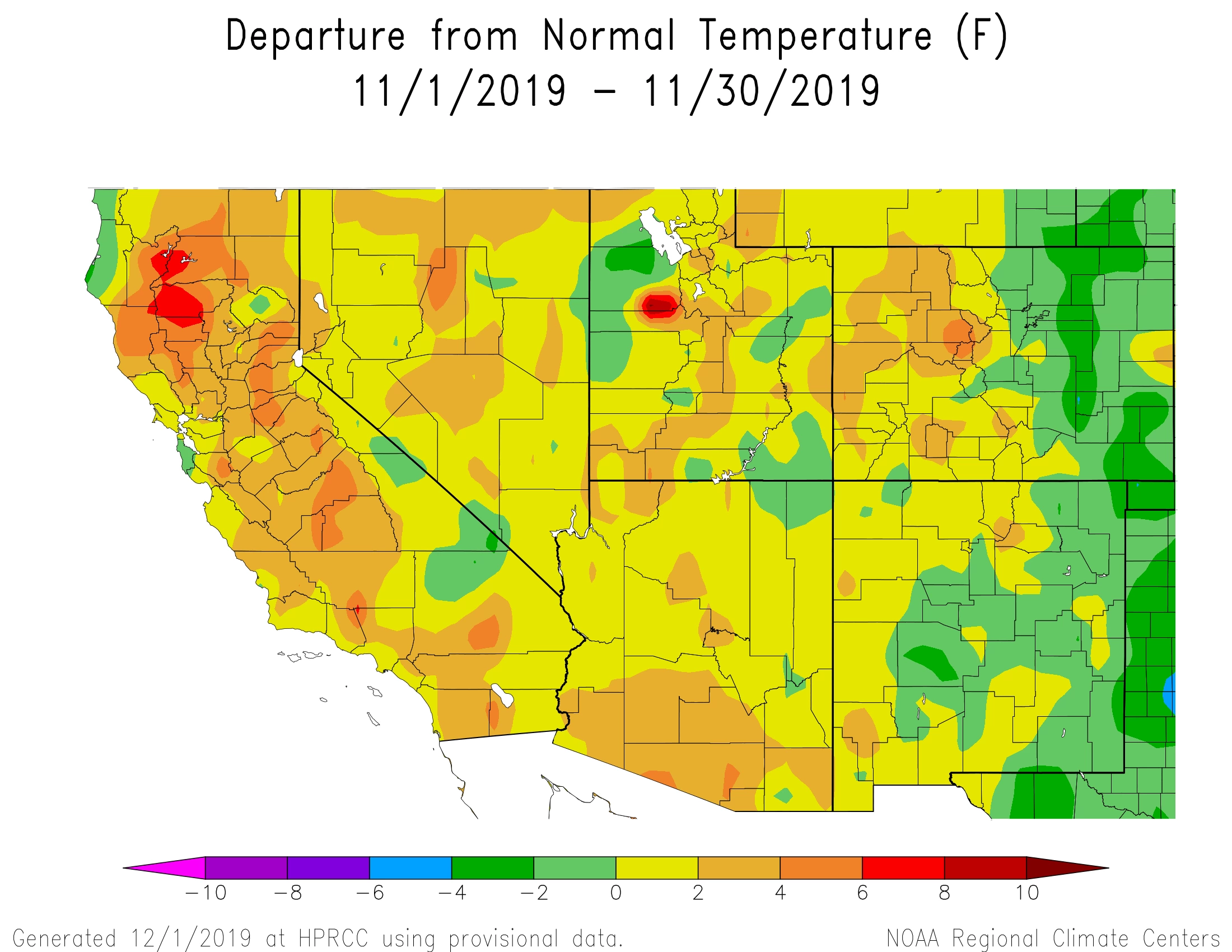

A Recap of November Temperature and Precipitation

Monthly average temperatures in November were within 2° Fahrenheit of the 1981-2010 average for much of Arizona and New Mexico (yellow and light green areas on map). Most of southern and parts of north-central Arizona were some of the exceptions to this, as temperatures there were 2° to 6° Fahrenheit above average (orange areas on map). Vines in relatively warmer winegrape-growing areas, like the Sonoita, Willcox, and proposed Verde Valley American Viticultural Areas (AVAs) in Arizona and the Mesilla Valley and Mimbres Valley AVAs in southern New Mexico, may have argued against dormancy during the relatively warm first half of the month, despite the arrival of the first fall freeze in late October. Any such arguments were quieted with the relatively cooler second half of November.

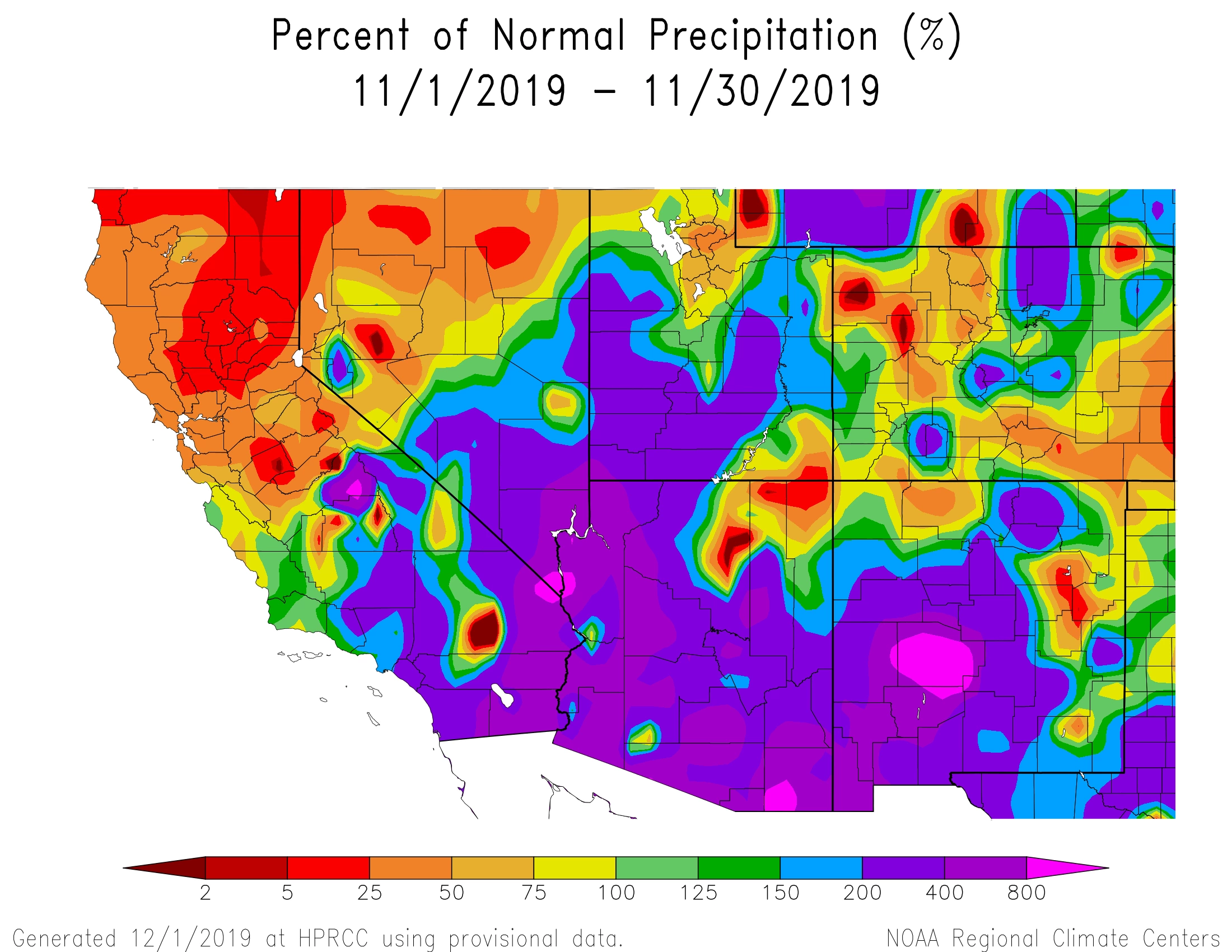

NOAA ACIS

Monthly precipitation totals were above 200% of the 1981-2010 average for almost all of Arizona and New Mexico (purple and magenta areas on map), with only extreme northeastern Arizona and northwestern and east-central New Mexico experiencing below-average amounts (yellow, orange, and red areas on map). Several storms crossed the region during the latter part of the month, setting precipitation records while providing a great start for increasing soil moisture in vineyards this cool season and guarding against delayed spring growth, which results from dry conditions and manifests as uneven bud break, stunted growth, reduced flower clusters, and other issues.

NOAA ACIS

The Outlook for December Temperature and Precipitation

There is a slight increase in chances for above-average temperatures across Arizona (light orange area on map), except for the northwestern part of the state where there are equal chances for above-, near-, or below-normal temperatures for the month (white area on map). Slight to moderate increases in chances for above-average temperatures exist for New Mexico as one goes from west to east across the state (light and dark orange areas on map). This is the initial backdrop for what is left of the first part of the dormant season, when vines are working to meet chilling requirements as part of their endodormancy state.

NOAA CPC

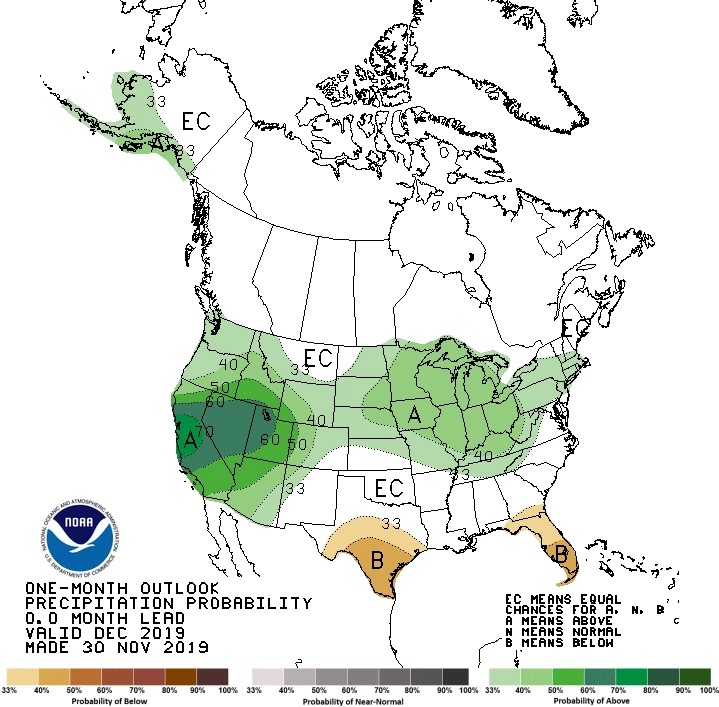

There are slight to moderate increases in chances for above-normal precipitation as one goes from southeast to northwest across Arizona (light and dark green areas on map), mostly due to the potential for a wet start to the month. A slight increase in chances for above-normal precipitation also exists for northwestern New Mexico (light green area on map), whereas equal chances exist for above-, near-, or below-average precipitation totals for the rest of the state (white area on map). Our fingers are crossed for continuing the increase in cool-season soil moisture that began last month.

NOAA CPC

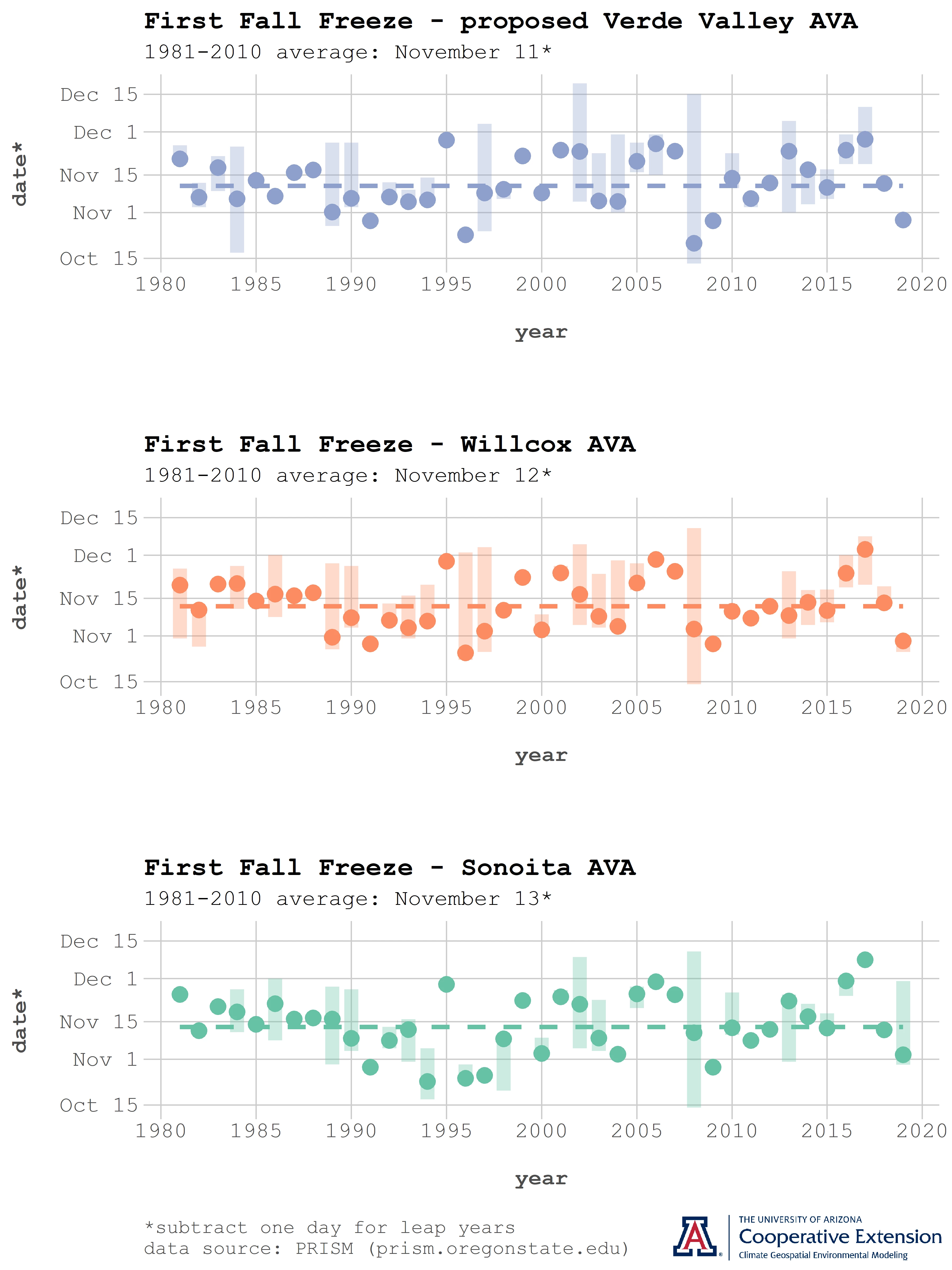

Another Look at the First Fall Freeze

How did the first fall freeze in 2019 compare to those of previous years? From the perspectives of the American Viticultural Areas (AVAs) in Arizona, the temperature dropped below 32° Fahrenheit for the first time this fall at the end of October for the Willcox and proposed Verde Valley AVAs (orange and blue dots, respectively, on figure) and at the beginning of November for the Sonoita AVA (green dots on figure). This is about one to two weeks earlier than normal (dashed lines on figure) for all three areas. These dates represent averages of first fall freeze dates for locations across these AVAs, except for the coldest and hottest spots.

In some years, the first fall freeze in an AVA occurs earlier in relatively cooler locations and later in relatively warmer ones. This is shown, for example, by the light-green bar in 2019 for the Sonoita AVA, which suggests that a few warm locations may not have dipped below freezing until later in November. In other years, no locations are spared, and the first fall freeze occurs throughout an AVA. This looks to be the case in 2018 and 2017 for the Sonoita AVA, as there is an absence of green bars for those years. In other words, colored bars in this figure represent the range of first fall freeze dates across an AVA for a given calendar year.

Over the past few decades, there looks to be a lot of similarity between the Sonoita, Willcox, and proposed Verde Valley AVAs when it comes to the first fall freeze. For instance, the earliest occurrence of the first fall freeze is middle-to-late October, and the latest occurrence is early December. The long-term average date for the first fall freeze is during the second week of November for the three areas. The AVAs also follow mostly the same up-and-down pattern from year to year, which reflects interannual variations of the regional climate.

Jeremy Weiss

A Bit More on Chilling Requirements

Meeting chilling requirements is thought to be an easy feat as most winegrape varieties – particularly those of Vitis vinifera – are often reported to only need a minimum of about 150 to 200 chill hours. The most simple and perhaps common way to keep track of chilling is by calculating a cumulative sum of hours between 32° and 45° Fahrenheit starting on November 1, an approach that has been around for at least 70 years in the context of fruit and nut trees.

More recent research points out, however, that this conventional chill model does not work as well in regions where daytime high temperatures frequently reach well above the chilling-temperature range. Such daytime warmth can effectively negate some of the accumulated chill hours. For such regions, a dynamic model incorporating this complexity is recommended.

Dynamic chill models are now being used for vineyard issues like predicting insufficient chilling in warm-winter regions, which can lead to irregular bud burst, flowering, and, ultimately, lower yields. Although that likely is not an issue for winegrape growing in Arizona and New Mexico, it still is important to pay attention to chilling requirements here. Once met, vines shift from a state of endodormancy to ecodormancy, and begin losing cold hardiness while accumulating heat units that determine when bud break occurs. If a cold snap takes place during ecodormancy, freeze damage to vines can occur even though the plants have not yet leafed out. We guess this might have been possible in late winter of 2011 and 2013 in relatively warmer growing areas of the region.

"Vineyard in the Snow" by Phil Roeder is licensed under CC BY 2.0

For those of you in southeastern Arizona, Cooperative Extension manages an email listserv in coordination with the Tucson forecast office of the National Weather Service to provide information in the days leading up to agriculturally important events, like the first fall freeze and extreme winter cold. Please contact us if you'd like to sign up.

Please feel free to give us feedback on this issue of the Climate Viticulture Newsletter, suggestions on what to include more or less often, and ideas for new topics.

Did someone forward you this newsletter? Please contact us to subscribe.

We thank all of you for supporting our climate-viticulture project this past year, and we look forward to continuing it in 2020. Have a wonderful December and holiday season!

With support from: