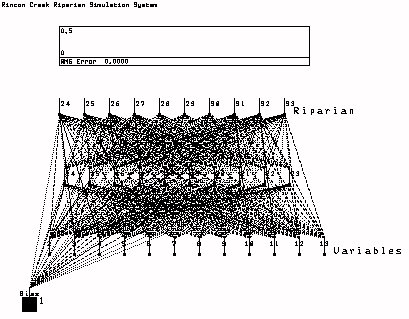

Figure #1 - Processing element and transfrer functions

The section of the report will present both guidelines for the type of data that should to be collected for the long term development of the dynamic model to assess impacts on the riparian system along Rincon Creek. Since there have never been any consistent and distinguishable bench marks for which to georeference any aerial photos, particularily ones that vary in resolution and scale, very little can be done to demonstrate a dynamic model that identifies and simulates change to the Rincon Creek Riparian area. Instead, this section will outline the components of a conceptual model that will be used in the future to predict impacts along the rincon creek as a result of encroaching development. This approach used GIS, high resolution aerial imagery, pattern recognition techniques for classifying and assessing current environmental conditions such as neural networks and field methods for collecting such data.

The recent explosive development of resource planning related technology, from remote sensing and digital database development to spatial analysis, has created new opportunities for landscape planners. Computer based Geographic Information Systems (GIS) provide the user with a variety tools with which to manipulate large digital database, execute simple models and display the results. Other technological advances in computer science, such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) are providing new tools with potential applications in spatial data analysis and theory development. These technologies not only promise to add accuracy and speed to the existing landscape planning process, but also to provide a medium for the development of new theory in understanding complex, natural systems and techniques to inventory and assess them (Deadman et al. 1995).

Growth and development of computer related technologies have brought incredible changes to our personal and working lives in the last ten years. These technologies have greatly increased the speed and efficiency of many work related tasks. Artificial Intelligence promises to further improve the effectiveness of these tools by bringing a degree of intelligence to many computer based technologies. Initial steps in this direction have been made in such fields as robotics, natural language processing, and medical diagnosis (Charniak and McDermott 1985).

Artificial Intelligence has been defined as the study of mental faculties through the use of computational models (Charniak and McDermott 1985). The word intelligence can be misleading because it implies the creation of a computer that thinks and acts as we do. But the creation of a computer which acts like a human is only a theoretical goal which has little bearing on most current artificial intelligence research. Much of the current AI research is devoted to making computers do things that are automatic for us, such as vision or voice and object recognition. At this point in time, computers and humans are capable of performing quite different tasks very efficiently. While computers can perform mathematical calculations much more efficiently than we can, humans are far better at such tasks as vision and pattern recognition. By developing these human capabilities even in a limited way and combining them with the powerful computational capabilities of computers, it is possible to create AI tools with useful applications.

Research in AI has progressed in numerous directions and resulted in the development of a variety of commercially available software packages including Artificial Neural Networks, Genetic Algorithms, Expert Systems, and Cellular Automata. Some of these packages have already been utilized in spatial modelling applications. For example, cellular automata have been utilized in combination with a GIS database to model changes in residential settlement patterns over time (Gimblett, 1989, Deadman et al. 1993). All of these new applications have promising applications in landscape planning and analysis.

The development of commercially available, user friendly neural net packages in the late eighties led to an explosion of studies which investigated their utility in a wide variety of applications. Neural networks have been applied in such diverse fields as voice recognition and astronomy. Applications in landscape related research have included; modelling scenic beauty from extracted landscape attributes (Bishop 1996; Wyatt et al. 1994; Yulan et al. 1996), suitability analysis for forest management (Gimblett et al 1994, 1995), and suitability analysis for development (Sui 1992; Xu et al. 1990; Wang, 1992; Burley et al. 1995), recreation assessment (Guisse et al. 1997; Gimblett et al. 1993; Pattie, 1993), vegetation classification and assessment in arid environments (Deadman et al. 1997; Kunzman et al. 1997; Skirvin et al. 1997; Zhang et al. 1997), moisture prediction for fuel loading (Ball, 1997) and water harvesting system in arid ecosystems (Sanchez et al. 1997). Numerous publications and conferences have addressed theoretical and applications based issues surrounding neural networks. While most of these publications provide excellent background information, the above noted NN examples have been successfully used to study natural resource problems in arid environments. In addition these applications have all be developed in conjunction with GIS and remote sensing imagery and have had astonishing results.

The basic processing element of the Neural Network is known as the neuron or node. This processing element corresponds in theory to the individual neurons of the nervous system. The processing element is broken into two components, the internal activation function and the transfer function (DuBose and Klimasauskas 1989). Internal activation can be calculated in a number of ways. But it typically operates through a summation type function which adds up the values of incoming messages multiplied by a specific connection weight. The resultant output of the internal activation is sent to the transfer function which determines whether or not the processing element will send an output message (See figure #1).

Once the network has been trained on the training set to respond with the correct output to a variety of inputs, then the net can be fed the full data set for interpretation. The network will go through the complete data set only once, imputing each set of data and providing the appropriate output. Neural Networks can be trained to interpret data in a variety of forms including, categorical data, discrete data or continuous data. Neural networks are able to handle data which is noisy or incomplete.

Neural networks have not always enjoyed the widespread interest that they do today. Only in the last ten years or so have researchers recognized the inherent advantages of neural networks. For a period of time in the sixties and seventies, neural nets sat largely undeveloped while AI research proceeded in other fields such as Expert Systems. The Expert System, or knowledge based system, is a computer program that mimics the human reasoning process, relying on logic, belief, rules of thumb, opinion, and experience (Plant and Stone 1991). In the rule-based expert system, the knowledge and experience of the expert are captured in a series of if-then rules which are used to solve problems (Plant and Stone 1991). In the expert system program a central inference engine draws on the rules that reside in a knowledge base to interpret information provided by the user and develop a solution. These systems were developed and used widely in such applications as disease diagnosis in medicine and pest management in agriculture. Expert systems have been utilized in landscape research applications such as the interpretation of Scenic Beauty based on the attributes of photographs (Buhyoff et al. 1994).

As expert systems developed, literature began to appear discussing the limitations that researchers had encountered. In particular, expert systems have a difficult time handling noisy or incomplete data. It was also found that some human knowledge is inexpressible in the form of rules and sometimes may not be understandable even though it can be expressed (Hoffman 1987). In addition, most human experts have difficulty expressing the tacit knowledge that they have acquired explicitly and completely. The difficulties associated with the development and implementation of expert systems has lead many researchers to begin exploring other techniques (Sui 1992).

Contrasted with the top down knowledge based approach of expert systems, neural networks take a bottom up data based approach to pattern-information processing. When relationships are understood and can be clearly articulated and computed, expert systems are appropriate. But when relationship requires a complex mathematical model that has not been developed yet, or when the relationship can be stated in general terms but is difficult to compute, neural network based models are appropriate (DuBose and Klimasauskas 1989).

The early stages of the rsource planning process require the collection and interpretation of landscape data in a number of themes. Such themes often include data pertaining to slope, aspect, soils, vegetation, and a variety of human modifications to the landscape. These diverse themes must often be interpreted in relation to one another in order to determine patterns in the landscape that are of interest to the goals of the planning exercise.

Traditional planning techniques such as map overlay analysis provide planners with a framework for relating these diverse themes to one another in reference to a specific question. Modern Geographic Information Systems even provide rudimentary modeling procedures, such as overlaying, for use with digital data. These early techniques provided planners with valuable if limited tools for landscape analysis. But the advent of AI technologies now presents us with the opportunity to perform more sophisticated analysis. In landscape research, neural networks have been employed in a variety of applications. Generally, the neural network is trained to respond to a variety of input variables, of spatial or non-spatial form, with an appropriate output which may take the form of a suitability rating, a vegetation classification, an estimate of recreation use,or a scenic beauty score. Examples of these applications are outlined below.

Sui (1992) utilized a back-propagation network to analyze the suitability of a number of land parcels for development. He compared the neural net based approach to a more traditional cartographic modeling based technique. Sui concluded that the neural net based approach was, inherently more objective and better able to handle noisy or missing data than the traditional approach. However, some questions regarding the neural net technique, particularly relating to the selection of an appropriate net architecture for the problem at hand, still remain. Wang (1992) utilized a neural network in a similar application to determine agricultural land suitability. The network interpreted input data in the form of numerical values, ordered textual symbols, and unordered textual symbols to determine the correct suitability class. Wang found the neural net to be an effective tool for agricultural suitability analysis in a GIS context.

Researchers with the Forest Service are utilizing neural networks in models to forecast occurrences of overnight stays in the National Park Service system on a monthly basis, and the USDA Forest Service system on an annual basis (Pattie, 1992). The neural network is trained on data which includes such variables as monthly climatic data, stream flow, U.S. Forest Service timber production, and historical trends in threatened or endangered species. In the future, the generalization of knowledge about backcountry recreation patterns to a broader class of management situations such as optimizing recreation carrying capacity, maximizing biological diversity and wildlife habitat represents an important process in learning from examples presented to neural network models (Pattie, 1992).

Other forest management modeling applications have combined neural networks with another AI technology, the genetic algorithm, to develop a resource management suitability model on part of the Hoosier National Forest (Gimblett et al. 1994). This study required the consideration of input data in eight mappable categories with an average of five variables per category. In total there are over 390,000 possible combinations of input variables for which a management prescription must be determined. Too many to consider manually. By training the neural network on fifty rules describing ideal selected input conditions and the appropriate management solution, the net is able to construct the missing rules as required during the running of the model. The resultant output is a more accurate, heterogeneous analysis, which is required for such intricate environments facing increasing pressures from a variety of users (Gimblett et al. 1994).

Neural network technology has also found its way into research on scenic beauty estimation. By training a neural network to associate scenic beauty scores derived from photo based surveys with geographic data extracted from the locations where the photos were shot, it is possible to develop a model that can extract scenic beauty scores from a GIS data base (Bishop, 1996).

Pertinent to this study is the work of (Deadman et al. 1997; Kunzman et al. 1997; Skirvin et al. 1997; Zhang et al. 1997). These studies have all successfully used NNís, GIS, remote sensing imagery and/or airbourne video in conjunction with field work to assess classify, assess and validate vegetation communities in arid environments. These models have demonstrated that using NNís in conjunction with imagery that there is a high degree of improved accuracy, time and money savings in data collection and can easily be reapplied annually to examine change to vegetation communities overtime.

Clearly, neural nets are suitable for a variety of applications. They are suitable for any application that involves pattern matching, including trend analysis, classification, and statistical clustering (Porter 1992). Neural nets are advantageous when the problem at hand is poorly defined and the data to be analyzed is noisy or incomplete (Gimblett et al. 1993). When the problem is extremely complex, the neural network can develop its own weighting scheme based on the relationships between variables thus reducing the task of user input in providing all known information about the problem (Gimblett et al 1993).

While there has limited application of NNís to explore the dynamics of riparian systems, the results of the research outlined earlier provide strong evidence that they could easily be applied in this situation. NNs used in conjunction with GIS spatial data could provide improved accuracy and prediction of impacts on the riparian system over time. While is it far to costly to spend years and years collecting data, an automated solution that examines the relationships between cause and effect is desperately needed in order to protect the integrity of the Rincon creek riparian system.

The conceptual model incorporates the use of NNs, GIS and long term monitoring to develop a tool to simulate changes to the Rincon Creek Riparian system overtime. The assumption behind the model is that by understanding both the changes in land use/cover conditions in the watershed surrounding the Rincon creek and the resultant changes to the conditions of the study sites over time, a model can be constructed to simulate conditions along the entire stretch of the creek. As more data is collected over the years at these specific study sites, change can be monitored and increase the predictive capability of the model. With these assumptions in mind, this model will attempt to define the patterns and relationships of physical measurable variables that define the range of conditions of the riparian system; the current land use conditions that surround and influence the riparian system ie. watershed; and the corresponding changes in each of the study sites.

The riparian system monitoring component provides three data inputs into the conceptual model. These three components are the biophysical (global), riparian systems expert-judgement and experimental systems field work (local). The biophysical component affects or alters the amount of vegetation and development. Existing conditions, or proposed changes to those conditions provide geographic information to the neural net classifier.

At the center of the model is the NN classifier. With the input supplied by the three riparian system monitoring components to the NN classifier, riparian health and productivity can be assessed. The second and third riparian system monitoring components, provide further training, refinement and validity to the prediction and classification outcomes of the conceptual model. Each of these components measures change to the system. The biophysical and expert components of the model serve as an initial training phase for the NN. The field work documented in this report provides initial output of the model to determine how well the NN has learned to predict the health of the system. The subsequent years of both acquiring biophysical data in the Rincon valley watershed and continued collection of field data in the designated study sites will be used to retrain and improve the performance of the riparian model. After a minimum of three to five more years of data collection and subsequent retraining of the NN model, predictive impacts along the Rincon creek can be made. It is at this stage that the biophysical data (landuse/landcover) collected for the surrounding watershed can be used as input into the model with resulting impacts along the Rincon creek as outputs.

Model outputs will be a measure of heath and/or productivity of the riparian system. This could be expressed as scalar set of thresholds that range from 1 to 10, defining the heath of the system. For the initial training of the neural net based model, conditions ranging from ideal to impared must be defined for the riparian system. Since little is known about these relationships the research team will define what constitutes a healthy riparian system, in terms of the type of measured variables described earlier in this report. A set of physical patterns or interaction rules that explicitly define the contribution of each variable to the scaler output will be derived. For example, under ideal conditions there would be no development, 100% vegetative cover, streamflow and sediment movement may be high, but the health of the riparian system may be excellent in terms of productivity, regeneration and seed production. This rule would be described like this:

Global Site Variables Experimental Site Variables Riparian Condition Output

(R1 Lct Lc1 Ld1 Is Dc) (S1s S1c S1d ..Sf Sm Gw) (Heath/Productivity Index)

|-----------------| + |---------------| = |-------------|

0 80 80 40 10 20 1 30 30Ö 40 40 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

where 0 represents development, landcover type mesquite, Percentage of vegetation coverage (80%), vegetative density (40%), infrastructure (10%), percentage of development (20%). experimental site variables vegetation species (type 1), coverage (30%), density (30%), streamflow (40cfs), sediment movement (40), depth to groundwater (2m). As a pattern, these variables represent a particular condition of the riparian system. The next ten values represent the current condition of the riparian system for each of the sites. The associated pattern combined represented in this case a healthy productive system. The first 0 of the riparian condition output represents a unproductive/severely damaged riparian system and the 10th node or value 1 represents a heathy/productive system In this case the 10th node is turned on which represents the later. Another way of describing this input pattern is like this:if the following conditions are encountered in one of the sites;

is set it equal to the 1st output variable:

There are potentially thousands of combinations of the measured data on site. The neural net will be trained to associate the input patterns with the output patterns.

The network will then be tested on the data from both the global set of site variables (watershed scale) and from microscale experimental field data collected from each of the experimental sites. This data will be analyzed by the neural net model to predict current heath/productivity conditions for each of the study sites. These results will be evaluated, training samples and outputs adjusted and the network will be additional trained to recognized and adapt to these new patterns. The purpose of this method is to first identify how accurate the network can predict the current conditions of the study sites based on the expert-based judgements of their conditions. Second, to increase the knowledge base and refine the predictive capability of the neural network by retraining on the data captured in the field.

The next several times the data is collected in the field, the same procedures can be used to build on to the knowledge based and refine the conditions and sensitivity of the neural network for predicting conditions of the study sites.

After several years of data collection the neural net model will have sufficient land use/cover patterns and detailed field work to predict the impact of changes occuring in the Rincon Valley, on the riparian areas. With this extensive knowledge based it should be possible then to collect land use/cover data as outlined above at the global scale and have the neural network predict for any particular stretch the of the rincon creek, the heath/productivity of the system. Since all geographic factors will come from aerial of GIS data, a resultant map of the heath/productivity can be created. Identifying which areas are healthy and productive and which ones are not, knowing what conditions and variables effect these conditons, it should be possible to develop management plans for restoring the impacted areas to healthy/productive systems.

The validity and accuracy in the predictions of the model described above for identifying the health/productivitiy of the riparian system can only be accomplished with established procedures to collect and extract pertinent data over the next decade. The neural net solutions will only be as good as the data that it is trained on and this data must be collected consistently and accurately for incorporation into the model. To ensure this will occur, this report has already outlined field data collection methods for the study sites, but the following guidelines have been established collecting global spatial data in the Rincon Valley for the model.

Permanent monitoring points have been established using GPS along the Rincon creek for two purposes. First to revisit the exact locations where the initial field data was collected on each of the study sites to collect more data. This provides a mechanism for comparision and determining the degree of change that has occurred. Second as bench marks for georeferencing, high resolution, orthographic aerial photos as the Rincon creek and surrounding watershed. Since these permanent bench marks have not existed in the past, it is very difficult to reference any earlier photos and extract data with any high degree of confidence. These points be used for any future georeferencing of aerial data.

These aerial photos should be acquired every three years pending no development. When development begins to occur in Rocking K, photos should be shot once a year. All orthographic photos should be centered on sample study sites defined earlier in this report. These photos will be georeferenced and rectified using permanent GPS monitoring points as discussed above. Once the images have been rectified to a high degree of precision with the permanent monitoring points, spatially distributed data can be extracted. Repeating this procedure over the next several years may provide a statistically reliable method for assessing landuse change.

The final output from the predictive net is translated into a map, that identifies the current landuse /landcover conditions and the health/productivity of the Rincon creek riparian area.

The conceptual model presented above takes advantage of current technology to develop a predictive tool to assess the condition of the rincon creek riparian system. Using NNís in conjunction with GIS have some significant advantages over current techniques. NNs although sometimes slow to learn, once tested and trained can easily be applied and reapplied in similar situations, providing a more cost-effective means of classifying data than some conventional techniques. In addition, NNs are adaptive by nature, with real-time capabilities. NNs continually learn and store new patterns in data that are presented to the nets, and this give them more flexibility, universally applied classification capabilities.

The conceptul model presented in this section has been established to assist the academics and resource managers in addressing the problem of identifying and measuring impacts along the Rincon creek riparian system. The following are the advantages that result from applying the methodology:

Since there are relatively few individuals who can answer this question, what knowledge that can be gleened from research will be augmented with field work to acquire a better understanding of riparian systems. What is important about the conceptual model is that with more detailed data that exemplifies changes in the condition of a riparian system, a neural network will learn these changes, adapt and adjust itís predictive weights to provide optimal predictions in situations where only partial data is known. This situation arises in the case of the rincon creek where it is physically and economically impossible to gather data on every square foot of the creek. Having representative sites that exemplify a diversity of conditions of the system, it should be possible to extrapolate what is known in terms of impacts on those sites in other locations having similar characteristics.

A unique feature of using neural nets is that information about the landscape can be expressed as a pattern of variables the contribute to an outcome, but there is no assumption at the onset that there are interrelationships or dependance among the factors. The NN assumes independence among the input variables, but will identify which factors are strongly contributing to the overall solution. What may be found over years of data collection is that some of the variables identified and measured earlier in the study contribute very little to the convergence of the net and ultimately the optimal solution.

While many have hypothesized about the impacts of surrounding land use conditions on the riparian system, very little is still known or understood. By measuring the land use/cover conditions in the watershed overtime, it should be possible to make some statement about their impact. Increasing the amount of impervious surface, such as buildings, roads etc. and subsequent removal of vegetation hypothetically will supercede the balance of a healthy/productive riparian system resulting in adverse outcomes such as increased water, bank erosion and deposition as well as a decline in local vegetation. This model will allow the research team to explore these relationships and explicitly identify land use conditions over time that converge to supercede these thresholds, resulting in decline of the riparian system.

When the conditions surrounding the study sites change, what are the correponding changes in each of the study sites? Understanding then the changes that have occured on a watershed (global scale) and the impacts on the study sites (local scale), this model will be well equipments to learn these relationships and provide optimal predictions in situations where the detail site data have not been collected.

This has yet to be determined, but the conceptual model described above will assist in acquiring a better understanding of the impacts of development on riparian systems.

Ball, B. Fuel Moisture Prediction in Homogeneous Fuels Using GIS and Neural Networks. AI Applications. (Forthcoming). 1997.

Bishop, I. 1996. Comparing Regression and Neural Net Based Approaches to Modelling of Scenic Beauty. Landscape and Urban Planning 34: 125-134.

Buhyoff, G.J., Miller, P.A., Roach, J.W., Zhou, D., & L.G. Fuller. 1994. An AI Methodology for Landscape Visual Assessments. AI Applications. 8:1-13.

Burley, J.B. & T.J. Brown. 1995. Constructing Interpretable Environments from Multidimensional Data: GIS Suitability Overlays and Principle Component Analysis. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. (Forthcoming).

Charniak, E. & D. McDermott. 1984. Introduction to Artificial Intelligence. Addison-Wesley.

Deadman, P., Brown, R.D., & H.R. Gimblett. 1993. Modelling Rural Residential Settlement Patterns with Cellular Automata. Journal of Environmental Management. 37: 147-160.

Deadman, P. & H. R. Gimblett. Merging Technologies: Linking Artificial Intelligence to Geographic Information Systems for Landscape Research and Education. Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture. Iowa State University. Ames, Iowa. September 9-11, 1995.

Deadman, P.J. & H.R. Gimblett.. An Application of Neural Net based Techniques for Vegetation Management and Plan Development. AI Applications. (Forthcoming). 1997.

DuBose, P. & C. Klimasauskas. 1989. Introduction to Neural Networks with Examples and Applications. NeuralWare Inc.Pittsburgh.

Gimblett, H.R. 1989. Modelling in GIS: A cellular automaton to modelling the growth of urban and rural development. GIS National Conference 89. Ottawa, Canada.

Gimblett, H.R., Guise, A.W., & D.P. Kroh. 1993. A Spatial Model for Assessing Conflicting Recreation Values in State Park Settings. MAGIC-Arizona Geographic Information Council, Phoenix, Az, 19-20 August 1993.

Gimblett, R.H., Ball, G.L & A.W. Guise. 1994. Autonomous rule generation and assessment for complex spatial modeling. Landscapeand Urban Planning. 30:13-26.

Gimblett, R.H.., Ball, G.L. Neural Network Architectures for Monitoring and Simulating Changes in Forest Resource Management. AI Applications. Vol. 9, No. 2, 1995.

Guisse, A.W. & H.R. Gimblett. A Kohonen Counter-Propagation Neural Net Model for Assessing Conflicting Recreation Values in Natural Park Settings. AI Applications. (Forthcoming). 1997.

Hoffman, R. 1987. The Problem of Extracting the Knowledge of Experts from the Perspective of Experimental Psychology. AI Magazine, 8:53-67.

Kunzmann, M.R., H.R. Gimblett and P.S. Bennett. GIS, GPS and AI in Vegetation Classification Modeling in Chiricahua National Monument. AI Applications (Forthcoming). 1997.

Openshaw, S. 1993. Modelling Spatial Interaction Using a Neural Net. in Geographic Information Systems, Spatial Modelling, and Policy Evaluation. M.M. Fischer & P. Nijkamp eds. Springer Verlag. Berlin. pp.147-166.

Pattie, D.C. 1992. Using Neural Networks to Forecast Recreation in Wilderness Areas. AI Applications 6:57-59.

Plant, R.E. & N.D. Stone. 1991. Knowledge-Based Systems in Agriculture. McGraw-Hill.

Porter, M.L. 1992. Neural Nets Offer Real Solutions. AI Applications 6(1): 32-40.

Sanchez, I & R. Jasso. A Neural Network for Predicting the Performance of a Water Harvesting System in Arid Ecosystems. AI Applications. (Forthcoming). 1997.

Skirvin, S. & G. Dryden. Kohonen Self-Organizing Map Artificial Neural Network Classification of Landsat Data. AI Applications. (Forthcoming). 1997.

Sui, D.Z. 1992. An Initial Investigation of Integrating Neural Networks with GIS for Spatial Decision Making. Proceedings of GIS/LIS 92. San Jose California.

Wang, F. 1992. Incorporating a Neural Network into GIS for Agricultural Land Suitability Analysis. Proceedings of GIS/LIS 92. San Jose. California.

Wyatt, R. & R. Itami. 1994. Learning to appreciate : computer- based learning of the aesthetic appeal of mountain views using a simulated neural network. Proceedings of Resource Technology 94, University of Melbourne. Melbourne, Australia. September 26-30, 1994. pps. 247-260.

Xu Xiaomei & Yin Yongyan. A Neural Net Model for Forest Management. GIS Ď90 Symposium, Vancouver, British Columbia. March, 1990. pp. 501-506.

Yulan, Y, Jiann-Min, Jeng, H.R. Gimblett, T.C. Daniel, D. Fesenmaier. An Integration of Geographic Information Systems and Artificial Neural Networks for the Estimation of Vista Scenic Beauty Preferences. The Sixth International Symposium on Society and Natural Resource Management Conference. Penn State University. May 18-23, 1996.

Zhang, X., C. Li & Y. Yuan . Applying Neural Networks for Identifying Vegetation Types from Satellite Image. AI Applications. (Forthcoming). 1997.