Snakes in the Neighborhood

Effects

of urbanization on amphibians and reptiles

2003

Arizona Agricultural Experiment Station Research Report

![]()

Written by

Joanne Littlefield

The tiger rattlesnake (Crotalus tigris)

is found in the Southwest in arid,

rocky, desert foothills from sea level to 4,800 feet. It feeds on rodents

and will eat lizards as well.

Desert dwellers are a curious lot. Wewant sweeping vistas and inspiring sunsets. The haunting sound of coyotes howling in the distance evokes nostalgia for the wild West. But snakes are a different story. Most people don’t want them slithering through their backyards and perhaps into their homes. Each year the Rural Metro Fire Department is called to remove thousands of snakes from backyards in the city foothills as the parade of new houses marches farther into the desert.

Until a few years ago, if a developer in Arizona said “show me the data” about the potential impact of development on wildlife, there was very little solid research to offer. Yet most wildlife biologists agree that development is probably the main threat to wildlife in the state.

“When you take a bulldozer and grade off a piece of desert, then whatever was living there probably isn’t going to be there anymore,” says Matt Goode, a University of Arizona herpetologist with the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences School of Renewable Natural Resources.

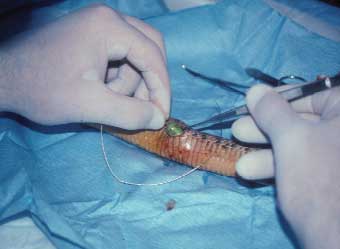

For five years Goode has studied the ecology and behavior of the tiger rattlesnake in Tucson’s Rincon Mountains around the eastern portion of Saguaro National Park. What he and his assistants have discovered could help developers as they plan for the future. Using radio telemetry, which involved placing transmitters into the body cavity of the snakes, they were able to track the snakes as they moved about.

“The snakes tend to overwinter on steep, rocky slopes, and then they go down into surrounding washes in the summertime, where they forage and mate,” Goode says. He notes that planners for a local resort have placed home sites on the precise area that the rattlesnakes use as a major travel corridor between the slopes and the wash.

“I guarantee you they’re going to have a lot of tiger rattlesnakes crawling through the resort after it’s built,” he predicts.

Because the tiger rattlesnake is not an endangered species, landowners are not required to comply with specific environmental regulations for it. Goode and his colleagues are not actively trying to stop developments, but rather are investigating how to make them more compatible with wildlife species in the region, even rattlesnakes.

“I don’t think any of us is going to be happy sometime down the road if all we do is populate the desert with people,” Goode says. The presence of wildlife is often considered one of the benefits of desert living.

Studies have shown that when removed from a housing development, snakes tended to travel to find their way back home. Some snakes stopped eating and even died.

“Translocating a snake gets it out of people’s yards, but will likely have serious consequences for the snake,” Goode explains. “What you get is a snake that moves around a lot more than it would have in the first place, because it’s trying to find its way back home. The key is to move the snake as short a distance as possible, such as just outside your yard. Then it will likely move on, but still be within its home range.”

Goode is currently studying the effects of urban development on amphibians and reptiles in the Tortolita Mountains, near the Rancho Vistoso/Stone Canyon development just north of Tucson. The golf course and surrounding landscape are already in place. Goode’s preliminary findings indicate that the golf course environment seems to attract snakes and lizards.

“Because it’s supplying water, which is in short supply in the desert, the golf course and surrounding landscaping are probably a boon to most animals,” he says.

By obtaining baseline data in places that are going to be developed, Goode and his research team can make comparisons to areas that are not going to remain undeveloped. This scientific framework should yield some important information on how urban developments affect amphibians and reptiles over time.

“Learning what it takes to coexist with wildlife is really what we’re after, says Goode, “and it’s going to take some enlightened attitudes on the part of the public. After all, the snakes were here first, right?”

Goode’s work is funded by the Arizona Game and Fish Department Heritage Urban Wildlife Program, which earmarks nearly $200,000 annually for projects related to urban wildlife conservation and education.

By placing radio transmitters in the body cavity of the snake, biologists are better able to gather information on feeding and breeding habits over time.

THE DESERT SOUTHWEST COOPERATIVE ECOSYSTEM STUDIES UNIT

The Desert Southwest Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit is a consortium of federal agencies, universities and non-governmental organizations in the Southwest Desert region (Arizona, California, New Mexico, Nevada, and Texas) hosted by the University of Arizona and the School of Renewable Natural Resources.

The partnership addresses research, educational and technical assistance needs for the management of federal lands. The objectives of the Desert Southwest Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit are to:

- Provide research, technical assistance and education to federal land management, environmental and research agencies and their potential partners;

- Develop a program of research, technical assistance and education that involves the biological, physical, social, and cultural sciences needed to address resources issues and interdisciplinary problem-solving at multiple scales and in an ecosystem context at the local, regional, and national level; and

- Place special emphasis on the working collaboration among federal agencies and universities and their related partner institutions.

CONTACT:

Matt Goode

(520) 626-2393

mgoode@ag.arizona.edu

Return to the Title Page

Return to the Table of Contacts

The University of Arizona is an Equal Opportunity/Affirmative

Action Employer. Any products, services, or organizations that are mentioned,

shown, or indirectly implied in this publication do not imply endorsement

by the University of Arizona.

Published January 2004

Return to College publication list