Drive to the Store or Purchase Online?

Consumer attitudes toward shopping venues affect marketing strategies

2003

Arizona Agricultural Experiment Station Research Report

![]()

Written by

Susan McGinley

Despite widespread advertising efforts, most Americans don’t yet fire up the computer and buy online. Shoppers still search for and buy books and apparel more often in physical stores than through the Internet.

Part of the reason may be consumer attitudes toward online shopping technology, according to a recent study in the School of Family and Consumer Sciences (FCS) at the University of Arizona. Shoppers who avoid online shopping may not trust that it’s safe, are not confident about how to do it, and/or think it is inefficient. Or they may just enjoy the physical experience of shopping in a traditional brick-and-mortar store.

“Of the total number of people who visit a website, only about 3.1 or 3.2 percent actually make a purchase, according to the State of Retailing Online 6.0,” says Mary Ann Eastlick, chair of the Division of Retailing and Consumer Sciences. “We’re trying to understand better the factors that are contributing to the limited adoption of online use. We want to find out how attitudes affect consumers’ coping strategies.”

In a study funded by IBM’s Global Services Division in 2001-2002, Eastlick, with colleagues Soyeon Shim, FCS director, and Sherry Lotz, associate professor, surveyed a cross section of American consumers to find out more about their searching and purchasing behavior. They wanted to know which channels people selected to find out more about products—physical stores or online retailers—and then where they actually bought the products.

The researchers developed and sent a written survey questionnaire to 5,000 consumers nationwide, a sample that was stratified to reflect demographic characteristics of the U.S. population. The study focused on discerning conflicting or paradoxical search-purchase habits and attitudes for buying books and apparel. “Search-purchase” channel-choice strategy refers to the various ways in which consumers select information channels to learn about and purchase products and/or services, according to Shim.

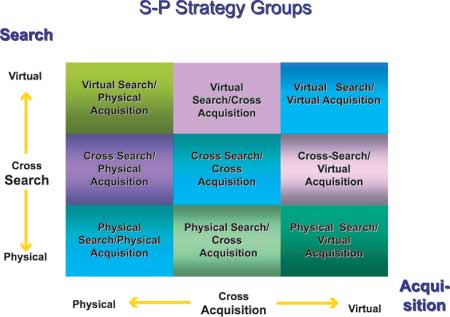

“We were able to group the respondents into nine segments based

on whether or not they searched only through online channels, only in

physical channels, or in both, contrasted with whether or not they purchased

online or in physical stores, or both,” Eastlick says.

Of the 519 respondents, the study found that the largest group preferred

to search and purchase only in traditional brick-and-mortar stores. The

next largest group searched both online and in physical stores, but purchased

only in physical stores, and the third largest group searched and purchased

in both channels.

“There were very few people in our study who did all of their searching and purchasing online,” Eastlick says. The questionnaire asked specific questions regarding consumers’ attitudes toward online shopping, their experience and level of skill in using computers to shop online, and their expertise in gathering and understanding information on products.

“What we found is that people who were Internet cross-searchers and purchasers felt that Web technology offered benefits like control over their shopping, saving them time and hassle,” Eastlick explains. “They weren’t very concerned about privacy issues in buying online. They had a higher technology competency and were more frequent users of cell phones and PCs—including email—than the other groups.”

Age was not a significant factor in the study, and neither was gender or ethnicity, although the majority of the respondents matched the general U.S. shopper profile: Caucasian, female, married, middle-aged, well-educated, with middle income.

Each consumer surveyed for this research fit into one of the nine searching and purchasing groups outlined above. “Cross search” means searching for products both online (virtual) and in physical stores. “Cross Acquisition” means buying in physical stores and online. The three largest groups in the study were the following:

Cross Search/Physical Acquisition: Consumers who tended to search online and in physical stores, but actually bought items in physical stores

Physical Search/Physical Acquisition: Consumers who preferred searching and buying in physical stores

Cross Search/Cross Acquisition: Consumers who searched in both virtual and physical channels, and bought in both.

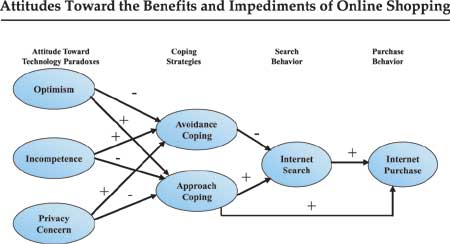

The researchers developed a model to evaluate consumer coping strategies. Those who were willing to integrate online shopping into their regular routine had what Eastlick and her team dubbed “approach coping” strategies. Those who refused to use or delayed using online shopping had adopted “avoidance coping” strategies.

Switching to online shopping and purchasing involves optimism in trying out the technology and the ability to use it successfully. The purchaser also needs to trust that the site is secure for credit card transactions and believe that the items are displayed truthfully on the screen. These attitudes lead to approach coping.

In turn, a negative attitude toward online shopping technology leads very strongly to delaying or refusing to shop online. People who perceive that online shopping takes too much time or is inefficient in helping them decide what to purchase will do most of their searching and purchasing of books and apparel in traditional channels. Thus they have adopted avoidance coping.

In a related study, Shim and Lotz found that a consumer’s search/purchase choices of market channels—physical stores, online—could be used as a reliable way to divide consumers into market segments.

“Because of the proliferation of multi-channel retailers and due to the power and efficiency of the Internet as a search-purchase tool, we argue that it is critical for retailers to understand newly emerging segments of their market, which can be differentiated by consumers’ search-purchase channel strategy,” Lotz says.

Research like this contributes to the retailer’s ability to influence

consumer attitudes toward their online offerings, according to Eastlick.

She believes such research can identify, for commercial retailers, strategies

they can use to encourage an increased adoption of online purchasing

habits among consumers.

“They’ve got to manage these negative, distrustful attitudes and reduce the risk for the consumer through methods such as strict enforcement of privacy policies and seals of assurance,” she says. In addition, these companies need to reduce the risks related to consumer incompetence by tactics such as making purchase websites easier to navigate, and introducing Internet kiosks, computers and other aids in stores. The goal is not to convert all shoppers to online purchasing, but to show them it’s an option.

“It took 100 years for catalogue sales to achieve 4.7 percent of total retail sales, excluding auto sales,” Eastlick says. “In contrast, online sales reached 4.5 percent of total sales in just six years. But when you look at consumer acceptance of online retailing, in spite of this quick rise, it’s low. We’re beginning to understand the factors that contribute to that low rate of acceptance.”

In the future, Eastlick, Shim and Lotz hope to examine customer attitudes

toward online shopping based on their actual experiences with individual

retailers. Will a bad experience with one online purchase cause the shopper

to avoid online shopping altogether, or just with that individual retailer?

Also, will a bad online experience with a retailer cause negative feelings

about the firm’s store and/or catalog operations among consumers?

“This is a new area of research,” Eastlick says. “It’s tough to develop good methods for looking at these questions, but we ultimately hope our findings will lead to the development of technology that makes shopping easier for consumers.”

This chart shows how consumer attitudes toward online shopping can lead either to approach coping (wanting to shop online) or to avoidance coping (deciding not to search or shop online). Someone who is optimistic toward the benefits of online shopping will develop approach coping. A person who is pessimistic toward online shopping will think of the drawbacks to it and decide to purchase in physical stores instead, which is avoidance coping.

CONTACT:

Mary Ann Eastlick

(520) 621-8696

eastlick@u.arizona.edu

Soyeon Shim

(520) 621-7147

shim@ag.arizona.edu

Sherry Lotz

(520) 621-1295

slotz@ag.arizona.edu

Return to the Title Page

Return to the Table of Contacts

The University of Arizona is an Equal Opportunity/Affirmative

Action Employer. Any products, services, or organizations that are mentioned,

shown, or indirectly implied in this publication do not imply endorsement

by the University of Arizona.

Published January 2004

Return to College publication list