Thoroughbred:

Racing Breeds, Rules and

Regulations

Time --- It's All Relative

By Lucinda Lovitt

Time is of the essence. At least that's what some people think. Racehorses, however, are not as conscious of time as their human counterparts. How fast a horse goes depends a little bit on training, a little on luck, and a lot on class. While it is important to understand how horses are timed on the track, both during the races and morning workouts, understanding your horse's class and running style will tell you much more about a workout or race than your stopwatch.

- Let's say your trainer calls to

report on your horse's morning workout. "He worked six furlongs in

Time is frequently used as a measure of how a horse is preparing for a race or has performed in the past. To some, results from a stopwatch indicate when a horse is ready to run, while others prefer to use workout times along with visual impressions to determine preparedness for racing. What makes time, as it relates to racehorses, so subjective is that time., only measures how fast the horse is rung, not the manner in which he is traveling.

The factors that contribute to how fast or slow a horse works during the morning are limitless. Probably the most important factor is your horse's running style. If your horse is a closer (comes from off the pace), he may work the first 1/2 mile to 5/8th slowly and then work the final 1/8th a second or two faster. If your horse is a sprinter, each 1/8th of a mile may be a second faster than the work of an average horse. Horses that work in company (with more than one horse) exert more energy than those working alone, which could contribute to a faster workout.

Horses, on average, run 1/8th of a mile in 12 to 13 seconds.

At six furlongs, a fast workout may be between

Additionally, the surfaces on which your horse works and runs and track conditions contribute to the time of a workout or race. Dirt races are typically faster than turf (grass) races and dry tracks are usually faster than muddy tracks.

As the morning turns into afternoon, final times take on an

added significance, especially to fans in the grandstand and owners in the box

seats. A maiden winner who runs six furlongs in

Lucinda Lovitt serves as TM Owners' Liaison

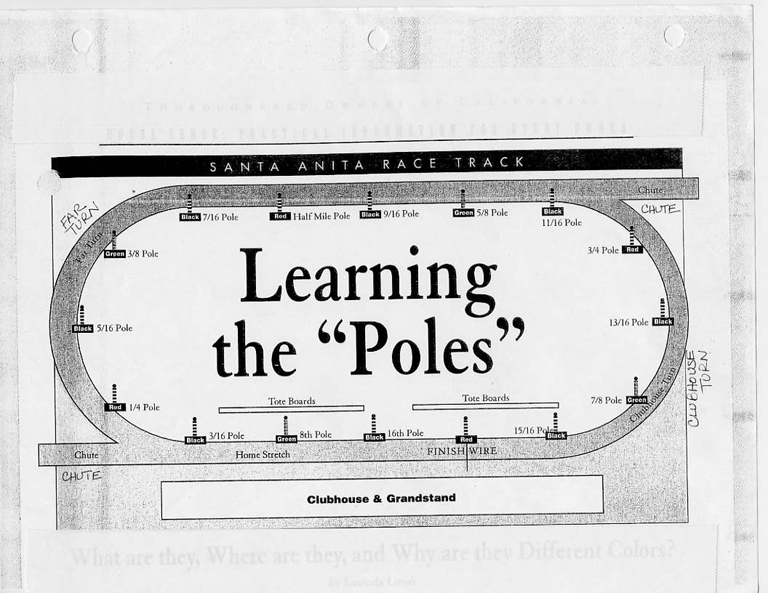

THE "POLES"

What are they, Where are they, and Why are they Different Colors?

By Lucinda Lovitt

It's a beautiful Saturday morning in

As you watch the sea of horses galloping by, you ask yourself "How will I be able to time my horse, and how will I know how far it has worked?" To answer this question, and have a better understanding of morning workouts, it's important to know the poles, or mile-Fraction markers on, the racetrack.

The placement of poles on the racetrack is crucial to those involved in training and racing Thoroughbreds. Jockeys, trainers, and owners use the poles to measure how far a horse has traveled, and how far they have to go.

The easiest way to acquaint yourself

with the poles is to start at the finish line, or "wire", and count

the poles backward, orclockwise. In

For example, let's look at Santa Anita's mile track (see diagram). Start at the wire, and begin to count the poles backwards. The first pole (black) you reach is the 1/16th mile marker, the second pole (green) is the 1/8th (or 2/16th) mile marker, the third pole (black) is the 3/16th mile marker, and the fourth pole (red) is the quarter-mile marker. As you continue to work your way backward around the track, add 1/16th of a mile to every pole you reach. Doing this, you will pass the 5/16th pole (black), 3/8th pole (green), 7/16th pole. (black), and the 1/2 mile pole (red). Continue to count your way around, passing the 3/4 pole (red) and finally back to the finish line, which would be the fourth and final 1/4 mile marker. If you are having trouble, try remembering the order of the colors of the poles with this acronym, B.G.B.R. (Black, Green, Black, Red).

However, not all tracks in

Armed with this knowledge, you'll now know when to start and stop your stopwatch when your trainer informs you your horse is going to- work seven furlongs from the 3/4 pole.

THE TRIPLE CROWN:

Excerpt From The Most

Glorious Crown

Introduction

A small red box, with gold snap-lock and hinges, sits atop a

tall green safe in the posh offices of the Thoroughbred Racing Associations, in

Each side of the trophy represents one of the three races,

which a single horse must win in a single year to earn the title. Often

referred to as the three "jewels" in the Triple Crown, they are the

Kentucky Derby, the Preakness Stakes, and the Belmont

Stakes, three of the oldest classics of

From 1949 through 1972, every spring, the vase had been sent to its designer, Cartier, Inc., to be burnished to a painfully brilliant gloss, in anticipation of the next winner of the trophy. On the second week of June, in each of these years, the vase was returned to its red box, which was returned to its perch atop the tall green safe in the posh offices of the TRA, as yet another season passed without a recipient.

The fact is, from 1875 through 1974, the years that all three races have been in existence simultaneously, only nine horses have won the Triple Crown, making it the most elusive championship in all of sports. It was last won in 1973, and the members of this exclusive club of titleholders are: Sir Barton (1919), Gallant Fox (1930), Omaha (1935), War Admiral (1937), Whirlaway (1941), Count Fleet (1943), Assault (1946), Citation (1948), and Secretariat (1973).

In fairness to all Thoroughbreds, past and present, it should be duly noted that some extenuating circumstances ruled out at least eight possible winners. In 1890, both the Preakness and the Belmont Stakes were raced on the same day; there was a three-year hiatus in the running of the Preakness, from 1891 to 1893; Governor Charles Evans Hughes of New York banned racing in the state during 1911 and 1912, which blacked out the Belmont Stakes; and both the Kentucky Derby and the Preakness were raced on the same day in 1917 and 1922.

Although the Kentucky Derby is the most famous of the three

races, it is the youngest. It was first run in 1875, on land owned by John and

Henry Churchill, in

The Preakness is raced two weeks

later, at Pimlico Race Course,

Although it is the oldest of the three, the

The Triple Crown title was formally proclaimed in December

1950, at the annual awards dinner of the Thoroughbred Racing Associations in

Credit for initiating the movement to proclaim a Triple Crown is given unofficially to Charles Hatton, the venerable columnist of the defunct Morning Telegraph and present Daily Racing Form. It was in the early 19309 that his copy began to include the phrase "triple crown," whenever he wrote about the Kentucky Derby, Preakness, and Belmont Stakes. As with many newsmen who eschew the touch-typing system in favor of the two-finger hunt-and-peck method, Hatton tired of having to spell out the names of the races in his copy every spring, and evolved his own shortcut by referring to them collectively as the "triple crown" races. "It was rhetorically more acceptable," he claims. In time, his fellow fourth-estaters picked up the cue, and the phrase became so popular that more and more owners began to point their horses toward winning the triad of races. By 1941, newspapers were hailing the feat with banner headlines, such as: "Triple Crown to Whirlaway; Easily Takes Belmont Stake."

The Triple Crown is not an

American racing innovation. Rather, it came to us from

The Two Thousand Guineas is raced

at

The importance of the Triple

Crown races grew apace with the evolution of the science of breeding

Thoroughbred horses. Once the Thoroughbred gained a foothold in

"The term 'Thoroughbred' as applied to the horse is universally accepted and recognized as applying specifically and lirnitedly to the equine strain which traces to the Arabian, Barb or Turk," say the editors of Call Me Horse, a book which devotes itself to horse racing and breeding.

The Arabian, or what is referred

to as the Southern Horse (hotblood line) in the

evolution of the horse, was indigenous to

The Arabian became a favorite

mount of the Turks, who, with the Roman legions, brought him to the Continent

during their invasions. The horse also found his way across

At the outset in

The need for a lighter horse with

speed and dexterity was painfully evident during the Crusades when the great

knights suddenly found themselves completely outspread and outmaneuvered by the

swift, streamlined Arabian flyers. One battlefield report said: "The

Infidels not being weighed down with heavy armour

like‑our knights were always able to outstrip them in pace, were a

constant trouble. When charged they are wont to fly, and their horses are more

nimble than any others in the world; one may liken them to swallows for

swiftness." Some of these flyers‑were brought back to

Although the first racehorses in

During the reign of the Stuarts

in the 1600s, Barbs, Arabs, and Turks were imported in great numbers. It was

between 1688 and 1729 that three famous stallions arrived in

The Byerly

Turk is thought to have been captured by Captain Robert Byerly,

in 1687, when he fought the Turks in

Organized racing in

Thereafter, aristocratic planters

in

From the beginning, and

continuing until the Civil War, racing in

After the Civil War, American racing went through a refining process. Speed became the goal and the British system the model. For one thing, distances were lowered to the classic mile and a half and then to the mile and a quarter and the mile. By the turn of the twentieth century, stamina no longer was most important, and the most common distance was three quarters of a mile. Finally, two‑ and three‑furlong dashes came into vogue for two‑year‑olds, raced at the beginning of the year and leading up to a mile and a sixteenth for the best of them by October. Jockey clubs sprang up in different states to regulate breeding and racing through uniform rules. Purses were increased, too, until special races, the handicaps and stakes, took on added significance.

The one major difference between American and British racing was the track. In England, all races are run on turf, which custom dates back to the early days when the nobility gallivanted over the countryside, while in America virtually all races are held on oval dirt tracks, most of which are a mile around.

Efforts to set up clusters of

races along the lines of the British Triple Crown also began after the Civil

War. In 1875, Colonel Louis M: Clark, the founder of Churchill Downs, tried to

promote the Endurance Handicap, Kentucky Derby, and Key Derby.

By the same token, it was the fierce competitive spirit of a

distinguished Canadian sportsman, who was most anxious for his horses to run in

the 1919

Thoroughbred Racing Trends

RACES

Distances |

Percentage of Race Offered |

Average Purse |

|

Under 6 F |

49% |

$14,000 |

|

6 F - under 1 mile |

14% |

$18,000 |

|

1 - 1 1/4 miles |

36% |

$26,000 |

|

over 1 1/4 miles |

1% |

$63,000 |

The

three-year-olds who have won racing's Triple Crown (Kentucky Derby, Preakness Stakes, Belmont Stakes):

YEAR HORSE JOCKEY TRAINER

1978

1977

1973 Secretariat Ron

Turcotte Lucien

Laurin

1948 Citation Eddie

Arcaro

Jimmy Jones

1946 Assault

1943 Count Fleet John

Longden Don

Cameron

1941 Whirlaway Eddie Arcaro Ben

Jones

1937 War Admiral Charles

Kurtsinger George

Conway

1935 Omaha William

Saunders Sunny

Jim Fitzsimmons

1930 Gallant Fox Earl

Sande Sunny

Jim Fitzsimmons

1919 Sir Barton John

Loftus H.G.

Bedwell

The

winners of the Kentucky Derby and Preakness who were

unable to complete the Triple Crown:

YEAR HORSE BELMONT

2008 Big Brown ninth Da'Tara

2004 Smarty Jones second Birdstone

2003 Funny Cide third Empire Maker

2002 War Emblem eighth Sarava

1999 Charismatic third Lemon Drop Kid

1998 Real Quiet second Victory Gallop

1997 Silver Charm second Touch Gold

1989 Sunday Silence second Easy

Goer

1987 Alysheba fourth Bet Twice

1981 Pleasant Colony third Summing

1979 Spectacular Bid third Coastal

1971 Canonero II fourth Pass

Catcher

1969 Majestic Prince second Arts

and Letters

1968 Forward Pass second Stage Door Johnny

1966 Kauai King fourth Amberoid

1964 Northern Dancer third Quadrangle

1961 Carry Back seventh Sherluck

1958 Tim Tam second Cavan

1944 Pensive second Bounding

Home

1936 Bold Venture --- did not start ---

1932 Burgoo King --- did not start ---

Lead Changes

How Lead Changes Can Affect Performance

When your horse puts his best foot forward, that can give him an advantage

By Tracy Gantz

"He didn't change leads."

Just another jockey excuse? Not necessarily. If

your horse failed to change leads in the stretch, that loss of acceleration

could cost him the win.

Changing leads comes naturally to horses. When negotiating a turn at a gallop,

they will use their inside lead. In other words, turning left-as in a race-a

horse's feet will hit the ground in a four-beat cadence: right hind, left hind,

right front, left front. Thus, as you watch him, his left front foot is

"leading" him around the turn.

The correct lead is "the easiest method to get the shortest distance

between two points in the quickest way," said Dr. Ray Baran,

the racing association veterinarian at

At

But running an entire race on the left lead will tire a horse more quickly than

if he switches leads. So when a horse receives his first lessons, before he

gets to the racetrack, he learns to switch to his right lead in the

straight-aways. When he does it correctly, a horse can surge past his rivals,

especially if the competition doesn't change leads.

"When they switch to the right lead, it gives them a burst of

energy," said trainer John Sadler. "It's very important."

Many people concentrate on whether a horse changes leads in the stretch

driving to the finish line, but changing to the right lead down the backside

can help a horse as well.

"It's especially important for horses that have the propensity to stay on

their left leads in the lane," McCarron said.

"If you don't get them to change down the backside, they're already going

to start to get tired before they even change up at the head of the lane. Then

if they don't change, now you're adding fatigue on top of fatigue and they're

going to hang and stop."

McCarron recalled the Triple Crown battles between Affirmed and Alydar in 1978. "I can't help but think that if Alydar had changed leads in any one of those races, he might have had a little better chance of getting by Affirmed," said McCarron, who won the 1987 Kentucky Derby and Preakness aboard Alydar's son Alysheba.

Not every horse needs a lead change to win, however. Arazi

burst into prominence by winning the 1991 Breeders' Cup Juvenile and never

switched leads in the stretch. Point Given in this year's Preakness

switched leads close to the wire, but had already put away the rest of the

field.

McCarron rides a talented filly for trainer Ron McAnally, Janis Whitman's Beautiful Noise, who also doesn't

always need to switch leads. "She's done something that in 27 years of

riding I never had a horse be able to do," McCarron said. "Twice she has run 71/2 furlongs on her

left lead and won. She's very, very stubborn about changing leads. She's done

it her whole life." The jockey has learned not to push the filly to change

leads. "I can interrupt her momentum by fighting with her," he said.

Normally, though, trainers and jockeys try to convince a reluctant animal to switch. Sadler said he has improved horses by getting them to switch leads. He added that it's important to have a good exercise rider who can help teach the horse in the morning, "and then you've got to have the jockeys working with you in the afternoons."

Both Sadler and McCarron said that the keys to a successful lead change are the bridle and the rider's weight, not the whip.

When McCarron needs to ask a horse for a lead change, he first takes a stout hold of the horse's head. He uses the reins to steer the horse a little to the right, then back to the left, and then a more abrupt signal to the right. "You might see the head move," he said, "but I don't necessarily want the horse's body to float out and go into the path of somebody else. My duty, my responsibility is to make sure I keep the horse straight."

Those signals with the reins put tension on the bit, which will usually get a horse to switch to his right lead. If that doesn't work, "then I involve my weight," McCarron said. "I'll lean one way or the other in the same sequence-a little bit right, a little bit left, and then-boom-back to the right again. Angel Cordero taught me that one a long time ago."

While some horses are just reluctant to change leads, it can sometimes indicate a soundness problem. Dr. Baran said if a horse that previously showed no difficulty changing leads suddenly won't change, "it might mean he's comfortable in that lead and he's hurting in that other leg somewhere. You'd better investigate it."

Sadler watches lead changes when he looks at 2-year-olds in the training

sales. "This year I saw a horse sell at Barretts,"

he said. "The first preview, he went down the stretch in his left lead.

The second preview he went down the stretch in the left lead. I still liked the

horse. We vetted him, and he had a ton of problems." The horse ultimately

started for someone else at

Sadler also pays attention to sale prospects that change leads too often

because "usually it's a sign of sore shins," he said.

"I had one really good horse that didn't switch leads a lot-Olympic

Prospect," Sadler said. "I think it was because he had problems and

he felt more comfortable in his left lead. Also, he was so big that it was kind

of an effort for him to switch. So he won a lot of races on the left lead. They

can do it, but it's rare."

Sadler has also ridden jumpers, who must leap obstacles quickly and turn both to the left and to the right. "You're going for time, so you're turning in the air," he said. "If you want to turn left, you need him to land on his left lead." Lead changes are such a sign of an athletic horse that they are often part of Olympic dressage competition. And Dr. Baran cited the importance of lead changes when a horse cuts cattle.

"Sometimes you look at a particularly gifted horse, and they'll switch leads just so smoothly," said Sadler. "Those are the really special ones."

Tracy Gantz serves as TOC's

Deputy Director for